June 14, 2002

Fires From Hell, Views From Heaven

By MICHAEL JANOFSKY

|

| Agence France-Presse |

| Smoke from the Hayman fire, Colorado's largest on record, billowed near a ranch south of Denver on Tuesday. |

|

| Kevin Moloney for The New York Times |

| Kurt Kyle of Sedonia, Colo., loading his pickup and preparing to head north to his parents' home in Denver to escape the Hayman fire. |

|

| The New York Times |

| The Hayman fire picked up its pace on Tuesday after slowing. |

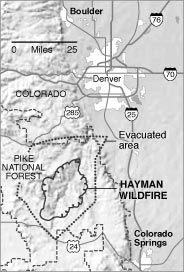

SEDALIA, Colo., June 11 — The call from a county official came at 4 p.m. on Monday as the Hayman wildfire moved quickly north through the Pike National Forest. The message was simple: Be prepared to evacuate.

Like others who got that message, Kurt Kyle and his family snapped into action, filling a van and a pickup truck with almost everything they own except appliances and large furniture and driving it all to the home of Mr. Kyle's parents in Denver, about 30 miles north.

Today, as the fire crept to within 10 miles of their home, the Kyles' effort took on added urgency. They loaded the van with televisions, stereos, an air compressor, even a favored pair of cowboy boots, and prepared to take the trip again.

"We just decided to move as much as we could," Mr. Kyle said, peering over a wooded ridge to the west that separates his 5,000-square-foot home from a wildfire that is now the largest in Colorado history. "It's an eerie feeling to think about a fire just over the back ridge. It's hard to think we could leave today, come back tomorrow and everything would be gone."

Thousands of Colorado families were in the same situation as six wildfires continued to burn across the state, with two others that had blazed as recently as Monday now contained.

President Bush assured Gov. Bill Owens in a telephone conversation today that federal emergency funds would be made available as needed. Mr. Owens, Interior Secretary Gale A. Norton and Joe M. Allbaugh, director of the Federal Emergency Management Agency, then toured affected areas by helicopter, and afterward Ms. Norton, former attorney general of Colorado, said: "It's very disturbing to me to see areas I've loved for years burned or endangered. Above all, there were so many homes right in the path of the fire."

With temperatures dropping, humidity rising and winds shifting overnight, the northeastward march of the Hayman fire — named for an old mining site where it erupted on Saturday — slowed for a time. But it picked up pace again during the day as temperatures rose and humidity fell.

With winds rising, firefighters were pulled off the front lines for a second consecutive day because of the intensity and unpredictability of the blaze, which has now consumed more than 85,000 acres and is completely uncontained.

Officials here in Douglas County and in adjoining Jefferson and Teller Counties evacuated some areas today and warned residents in others to be prepared to leave at a moment's notice. Already the fire has forced hundreds of people from their homes.

Part of the challenge of fighting the fire is the growing number of people like the Kyles who have been drawn in recent years to scenic remote settings near and within the very forests and wilderness areas that are now ablaze. For them, the ambient sounds of birds, the wildlife and the whistling winds are well worth the periodic stress caused by an approaching wildfire or, to some, even the wildfire itself.

"This is utopia," said Judy Tomkins, a medical writer whose family home is not far from the Kyles'. "It's a high price to pay to live here, but it is utopia, and I wouldn't leave because of it."

Don Smurthwaite, a spokesman for the National Interagency Fire Center in Boise, Idaho, said that throughout the West's "urban-wildland interface," fire officials now saw 10 times as many homes as there were 25 years ago in "areas that historically are vulnerable to fire."

"There's no question," he said, "that has very much complicated firefighting efforts of the last 20 years."

Fred Hubbard, the Colorado state forester, said the number of Coloradans living in areas at high risk of fire increased 30 percent during the 1990's, to 980,000 in 2000. The number of housing units in those areas rose 27 percent over the same period, to 475,000.

These changes in Colorado and elsewhere have helped make fighting fires far more expensive than ever.

"While you're dealing with structural protection and evacuations, you're not dealing with direct firefighting," Mr. Hubbard said. "Therefore, it costs more, and you oftentimes get a larger fire."

In the last eight years alone, the federal budget for wildfire programs has nearly tripled, to more than $2.8 billion in the current fiscal year.

And if drought persists in the West, the costs can only rise. Mr. Allbaugh said today that the Federal Emergency Management Agency responded with aid to 39 major fires last year. Already this year, he said, the agency has responded to 42.

A half-century ago, fires like those now plaguing Colorado would simply have been left to burn themselves out. Now, given the increasing number of homes in vulnerable areas, firefighting efforts have grown more urgent.

The challenge is made even more difficult, for firefighters and residents alike, by unpredictable changes in wind direction, a factor that has led officials fighting the current outbreak to err on the side of caution by warning large numbers to evacuate, or prepare to.

While the Kyles were packing enormous loads, Mrs. Tomkins and her husband, Rod, stuffed their cars with only sentimental items: "The Barbie dolls, Tonka toys, things from my children's childhood," Mrs. Tomkins said. "The rest of it is just stuff. So am I anxious? No. My feeling is if it goes, it goes. This is the American West. We'll rebuild from our ashes."

Randy and Linda Eisen said they felt the same way. They, too, were busy packing cars with important papers and sentimental items. Mrs. Eisen said she had spray-painted the family's telephone number on the sides of their three horses, in advance of setting them free if the fire bore down on them.

"We've lived here 18 years, and we've never given it a second thought," Mr. Eisen said of the periodic fires that jangle their nerves.

"It was a gross-looking house when we found it," Mrs. Eisen said. "But it was the land. That's why we came. God's not making any more of it, and you've got to get it while you can."