|

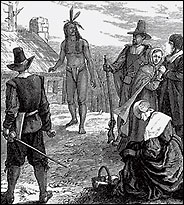

| Culver Pictures |

| An Indian visits the Plymouth Pilgrims in 1621. |

|

| Associated Press |

| Tribes from across the country protesting federal spending cuts in 1995. |

The United American Indians of New England are preparing for their 33rd annual ''National Day of Mourning'' near Plymouth Rock this week. Hundreds are expected to protest on Thanksgiving, according to Colin Calloway, a professor of History and Native American Studies at Dartmouth College, to counter what they call America's ''racism of the Pilgrim mythology'' built on commemorations of the famous 1621 feast that was shared with Chief Massasoit's Wampanoag tribe. In past years, speakers recited a litany of historical crimes and demanded recognition of present-day American Indian plights that include widespread poverty and ill health.

At least one group of Wampanoag descendants, however, is seeking another kind of notice. The Wampanoag of Mashpee, Mass., have for years petitioned to be formally recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. A tribe that can demonstrate, among other criteria, its continuous existence and its members' ancestral integrity is accorded virtual sovereignty and exempted from most state and local laws. And for hundreds of such current petitioners, federal status confers more than financial promise and the legal means to preserve their culture (through the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, say). Cora Tula Watters, chief of one 230-member band of the Shawnee Nation in Ohio, explained her group's effort to The Plain Dealer. ''If you don't have recognition, the reservation people look at you as a white person who wants to be Indian,'' she said. ''Basically, we're looking for dignity.''

THE CONFLICT

The Mashpee, like many tribes, have been frustrated for various reasons. N. Bruce Duthu, who teaches at Vermont Law School and is a member of Louisiana's Houma tribe (which has also unsuccessfully sought recognition for years), holds responsible the B.I.A.'s Bureau of Acknowledgment and Research, which he says is underfinanced and understaffed. Worse, he adds, ''historically, many of the staff had no academic training in tribal history or anthropology, and they used a litmus test that demands proofs of tribal continuity and political authority when those were precisely what came under assault through centuries of relocation and violence and forced assimilation. What's more, the bureau privileges the written record, but many tribes' most powerful evidence comes out of an oral tradition.''

Jeff Benedict, the author of ''Without Reservation: How a Controversial Indian Tribe Rose to Power and Built the World's Largest Casino,'' disagrees. ''Did European settlers control the history? Sure. It may be true that tribes have no written history from 300 years ago. But how about 50 or 60 or 100 years ago?''

THE STAKES OF THE GAME

Ever since passage of the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act of 1988, tribes have been able to operate casinos in states that allow them. Benedict says one result is that the business of recognition has become ''so inundated with casino and special-interest money that it's beyond broken.'' (In the last year, both the General Accounting Office and the Interior Department's inspector general have initiated investigations into recognition petitions.) Even if that's true in some cases, counters Anthony Gulig, an assistant professor of history at the University of Wisconsin at Whitewater, the historic redress is a net plus. ''The more people understand how dire things are in many parts of Indian country,'' he says, ''the more they'll realize how casinos have been a brilliant vehicle for the exercise of sovereignty.''

Duthu, who also concedes that gambling has exacerbated the recognition problem, argues that recognition can be isolated from gambling: ''Tribes still have to get permission from state regulators for casinos.'' To that, Benedict replies that courts have eviscerated states' power to block Indian casinos, adding: ''All the regular problems of casino development are compounded by sovereignty. The workers have no labor protection. Zoning laws, building codes, environmental regulations -- you name it, they don't apply.'' That's why Benedict supports reviving a recognition moratorium that was soundly defeated in the U.S. Senate last year. It's also why, as president of the Connecticut Alliance Against Casino Expansion, he's trying to prevent any additional casinos from being built in the state.

NUMBERS BEHIND THE STORY

• $12.7 billion in annual Indian gambling revenues, topping the take in Las Vegas.

• 562 currently recognized tribes; total membership, 1.6 million.

• 220 tribes in 39 states currently petitioning the B.I.A.

• 201 tribes with gambling operations (27 top $100 million per year).

• 11 members on the Bureau of Acknowledgment and Research responsible for 135 petitions received from 1991 to 2001 that ranged up to 100,000 pages each.

REWRITING HISTORY

Recent academic explorations challenge in other ways how Indians are recognized. The essays in ''The Backbone of History,'' edited by Dr. Richard H. Steckel and Dr. Jerome C. Rose, confirm earlier findings that Indian health declined markedly before the arrival of Columbus. In ''The Ecological Indian,'' Shepard Krech III, a Brown University anthropologist, portrays Indians aggressively engaged in commercial fur trading, which endangered local species. His study undermines ''visions of primordial environmentalists.'' But Krech stresses that an ''anti-Edenic'' revision of some history doesn't mitigate a level of present-day responsibility for a panoply of other historical wrongs. ''The co-optation of my book fascinates me,'' he says.

Even Benedict does not dismiss the legitimacy of the Thanksgiving protesters: ''That casinos somehow help pay back has serious power because it appeals to people's sense of fairness. We have a terrible track record of mistreating Indians in this country.'' He has no problem, however, separating that reality from his cause. ''We're not redressing historic wrongs by granting recognition to tribes like the ones in Connecticut,'' he says. ''That's just been cleverly used by the casino entrepreneurs to protect them against criticism.''

FOR FURTHER STUDY

• General Accounting Office report, ''Indian Issues: Improvements Needed in Tribal Recognition Process,'' November 2001.

• The National Museum of the American Indian.

• Waswagoning, Lac du Flambeau, Wis., the Ojibwe tribe's answer to Williamsburg.

• National Congress of American Indians: www.ncai.org.

• Connecticut Alliance Against Casino Expansion: www.connecticutalliance.org.

• ''Revenge of the Pequots,'' by Kim Isaac Eisler.

• ''Without Reservation,'' by Jeff Benedict.

• ''Playing Indian,'' by Philip J. Deloria.

Identity Politics

From 'The Houma of Louisiana: Politics, Identity, and the Legal Status of ''Tribe'''

(European Review of Native American Studies, 2001), by N. Bruce Duthu

Tribes involved in the acknowledgment process are essentially demanding the opportunity to revise the distribution of political authority and power; their challenge inevitably requires a reconsideration and revision of tribalism and indigeneity in the contemporary era. This challenge is rendered more severe by legal concepts entrenched in federal Indian law which treat tribes as ''wards'' of the federal government and by enduring social perspectives which view Indians as a powerless, vanquished or doomed people. . . . The acknowledgment process itself has become intensely politicized where opponents openly and brazenly challenge the bona fide claims of some Indian groups regarding their ''Indianness,'' fueled by beliefs that these groups are mere ''fronts'' for private interests seeking to establish gaming enterprises. The unparalleled success of tribal gaming operations by tribes in New England . . . has sparked a virtual feeding frenzy at the state and national level as politicians stumble over each other to introduce legislation to narrow the scope and nature of tribal sovereignty.

Copyright 2002 The New York Times Company

![]()