|

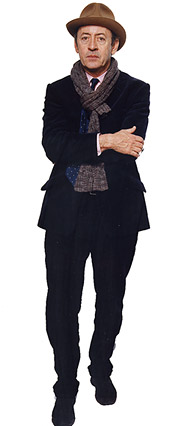

| Henry Leutwyler for The New York Times |

| Billy Collins. |

Q: As the poet laureate of the United States, I assume that you were invited to the White House symposium on poetry that was canceled recently once some poets began planning to use the event to protest war in Iraq.

Yes, I was. I would have gone if it had been held, to see what was going to happen. Politicizing the event has resulted in its cancellation and perhaps the end of literary events at the White House.

Could it really have that effect?

I don't know. I've always tried to keep the West and East Wings separate. I think the loss in this particular case was the opportunity to look at Whitman and Dickinson. In the middle of both of their lives occurred the central trauma of our country, the Civil War. And Whitman more or less jumped into action. He served as a volunteer nurse and wrote a poem, ''Vigil Strange I Kept on the Field One Night,'' where he holds the body of a dead boy and buries him. Whereas Emily Dickinson just stuck to her knitting, and her knitting just happened to do with immortality and death and the grave. It is a wonderful demonstration of the choice that poets have, to deal with the world around them in whatever way they think best.

So what sort of interaction have you had with Laura Bush's literacy program?

Well, none, really. I get invited to her book festival events. I have my Poetry 180 project, which I've made my main project. We encourage high schools, because that's really where for most people poetry dies off and gets buried under other adolescent pursuits.

What kind of authors have been at the book festival affairs?

Kinky Friedman comes to mind. He's one of theirs -- you know, a Texan. And Mary Higgins Clark. You know, popular authors, really.

We've had an actor as a president -- do you think we'll ever have a poet as a president?

Now there's a long shot. I think we'll definitely have a woman before a poet -- I mean, I don't think Gene McCarthy won any points when the public found out he wrote poetry. No, the public is probably more suspicious of poets than women, and maybe for good reason.

So much for Shelley's declaration that poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.

It's a delusion of grandeur. One of the ridiculous aspects of being a poet is the huge gulf between how seriously we take ourselves and how generally we are ignored by everybody else.

What was the last poem that really spoke to, or was embraced by, the American people?

I can't think of an antiwar poem that has spoken to the American people. There is one poem that has spoken to the American people, and that is ''Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening.'' That is the most popular poem in America. It was either that or ''The Road Not Taken'' that John F. Kennedy carried with him in his wallet on a piece of paper.

Do you imagine that President Bush reads much poetry?

I don't know what he reads. I hope he's not reading too much of it -- he should be busy doing other things, like running the country and maybe even keeping us out of war. I remember that when I read before Congress, someone commented that Dick Cheney on the CNN feed didn't appear to be paying a great deal of attention to my poem. I said: ''Well, I really wouldn't want him to. I would rather he concentrated on the affairs of state.''

If you could hand Bush or Cheney a poem right now, what would it be?

The poets who have written the best poems about war seem to be the poets whose countries have experienced an invasion or vicious dictatorships. Poets like Vaclav Havel, and Mandelstam and Akhmatova from Russia, and from Poland, Milosz, and the poet whom I am centering on, Wislawa Szymborska, a Nobel Prize winner. She has a poem, ''The End and the Beginning,'' that begins: ''After every war/someone has to clean up./Things won't/straighten themselves up, after all./Someone has to push the rubble/to the side of the road,/so the corpse-filled wagons/can pass.'' I would probably stand at the White House and hand out this poem.