|

| Mark Graham for The New York Times |

| Two years ago, the Arellanos, from left, Joe, Jackie, Jose, Irma and Anthony, paid $269 a month for health insurance. The price jumped to $339 last year and this year to $780, more than the mortgage payment. |

|

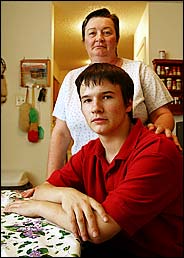

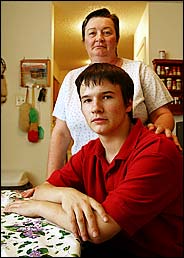

| Michael Stravato for The New York Times |

| Carol Johnston and her son Steven, who is losing his insurance covering the treatment of his learning and emotional disabilities. |

|

DALLAS — The last time Kevin Thornton had health insurance was three years ago, which was not much of a problem until he began having trouble swallowing.

"I broke down earlier this year and went in and talked to a doctor about it," said Mr. Thornton, who lives in Sherman, about 60 miles north of Dallas.

A barium X-ray cost him $130, and the radiologist another $70, expenses he charged to his credit cards. The doctor ordered other tests that Mr. Thornton simply could not afford.

"I was supposed to go back after the X-ray results came, but I decided just to live with it for a while," he said. "I may just be a walking time bomb."

Mr. Thornton, 41, left a stable job with good health coverage in 1998 for a higher salary at a dot-com company that went bust a few months later. Since then, he has worked on contract for various companies, including one that provided insurance until the project ended in 2000. "I failed to keep up the payments that would have been required to maintain my coverage," he said. "It was just too much money."

Mr. Thornton is one of more than 43 million people in the United States who lack health insurance, and their numbers are rapidly increasing because of ever soaring cost and job losses. Many states, including Texas, are also cutting back on subsidies for health care, further increasing the number of people with no coverage.

The majority of the uninsured are neither poor by official standards nor unemployed. They are accountants like Mr. Thornton, employees of small businesses, civil servants, single working mothers and those working part time or on contract.

"Now it's hitting people who look like you and me, dress like you and me, drive nice cars and live in nice houses but can't afford $1,000 a month for health insurance for their families," said R. King Hillier, director of legislative relations for Harris County, which includes Houston.

Paying for health insurance is becoming a middle-class problem, and not just here. "After paying for health insurance, you take home less than minimum wage," says a poster in New York City subways sponsored by Working Today, a nonprofit agency that offers health insurance to independent contractors in New York. "Welcome to middle-class poverty." In Southern California, 70,000 supermarket workers have been on strike for five weeks over plans to cut their health benefits.

The insurance crisis is especially visible in Texas, which has the highest proportion of uninsured in the country — almost one in every four residents. The state has a large population of immigrants; its labor market is dominated by low-wage service sector jobs, and it has a higher than average number of small businesses, which are less likely to provide health benefits because they pay higher insurance costs than large companies.

State cuts to subsidies for health insurance to help close a $10 billion budget gap will cost the state $500 million in federal matching money and are expected to further spur the rise in uninsured. In September, for example, more than half a million children enrolled in a state- and federal-subsidized insurance program lost dental, vision and most mental care coverage, and some 169,000 children will lose all insurance by 2005.

"These were tough economic times that the legislature was dealing with, and the governor believed in setting the tone for the legislative session that the government must operate the way Texas families do and Texas businesses do and live within its means," said Kathy Walt, spokeswoman for Gov. Rick Perry.

She noted that the legislature raised spending on health and human services by $1 billion this year, and that lawmakers passed two bills intended to make it easier for small businesses to provide health insurance for their employees.

Those measures, however, will not help Theresa Pardo or other Texas residents like her who have to make tough choices about medical care they need but cannot afford.

Ms. Pardo, a 29-year-old from Houston, said that having no insurance meant choosing between buying an inhaler for her 9-year-old asthmatic daughter or buying her a birthday present. The girl, Morgan, lost her state-subsidized insurance last month, and now her mother must pay $80 instead of $5 for the inhaler.

Rent, car payments and insurance, day care and utilities cost Ms. Pardo more than $1,200 a month, leaving less than $200 for food, gas and other expenses. So even though her employer, the Harris County government, provides her with low-cost insurance, she cannot afford the $275 a month she would have to pay to add her daughter to her plan.

When Morgan's dentist recently wanted to pull a tooth, Ms. Pardo hesitated. The tooth extraction proceeded, but: "I had to ask him, if you pull this tooth, will it cause other problems? Because if it does, I can't afford to deal with them."

Lorenda Stevenson said her choice was between buying medicine to treat patches of peeling, flaking skin on her hands, arms and face and making sure her son could continue his after-school tennis program. "There's no way I will cut that out unless we don't have money for food," she said.

Mrs. Stevenson's husband, Bill, lost his management job at

When their son, a ninth grader, needed a physical and shot to take tennis, Mrs. Stevenson turned to the Rockwall Area Health Clinic, a nonprofit clinic in Rockwall, a city of 13,000 northeast of Dallas. The clinic charged her $20 instead of the $400 she estimated she would have paid at the doctor's office.

"I sat filling out the paperwork and crying," she said, tears streaming down her face. "I was so embarrassed to bring him here."

A salve to treat her skin condition costs $27, and she pays roughly $50 a month for medications for high blood pressure and hormones. She does without medication she needs for acid reflux, treating the conditions sporadically with samples from the clinic.

Carol Johnston cannot afford even doctor visits. A single mother in Houston, she lost her job in health care administration in May and said she was still unemployed despite filling out 500 to 600 applications and attending countless job fairs.

Cobra would have cost $214 a month, or more than one-fifth of the $1,028 in unemployment she gets a month. As it is, her monthly bills for rent, car, utilities and phone exceed her income.

She got a 12-month deferral on her student loans, and Ford pushed her car payments back by two months. The Johnstons rely on television for entertainment and almost never use air-conditioning, despite Houston's muggy, hot climate.

Now Ms. Johnston's 16-year-old son is losing the portion of his insurance that covered treatment for his learning and emotional disabilities because of state cutbacks.

Ms. Johnston herself does not qualify for Medicaid, the government insurance program for the indigent, because her income is too high, the same reason she qualifies for only $10 a month in food stamps. "I worry, I worry so much about making sure my son is safe," she said.

As for her own health, Ms. Johnston has two cysts in one breast and three in another but has had only one aspirated because she cannot afford to check on the others. "Do I have to move to Iraq to get help?" she asked. "They have $87 billion for folks over there," she said, referring to money Congress allocated for military operations and rebuilding.

Experts warn that allowing health problems to fester is only going to increase the costs of health care for the uninsured. "As Americans, when are we going to realize it's cheaper to save them on the front end than when they get cancer and show up in the emergency room?" said Sandra B. Thurman, executive director of PediPlace, a nonprofit health clinic in Lewisville, Tex.

Many hospitals and neighborhood clinics here say that the well-heeled are now joining the poor in seeking their care. Emergency rooms are particularly hard hit, since federal law requires them to treat anyone who walks through their doors for emergency treatment, regardless of whether they can pay.

Public hospital emergency rooms are even harder hit, since private hospitals will move quickly to shift uninsured patients to them. And clinics for the poor are also seeing an increase in demand.

A clinic run by Central Dallas Ministries charges patients $5 for a doctor visit, $10 for medication and $15 if laboratory work is needed, but often settles for no payment from many of the 3,500 patients it treats each year.

"I'm not real optimistic it will get a lot better," said Larry Morris James, executive director of Central Dallas Ministries. "Demographic and economic trends tell you that it's probably going to get worse."

For Irma Arellano, the problem has already hit home. Mrs. Arellano is a secretary in the Royse school district northeast of Dallas, which provides her health insurance for $35 a month but offers no discounts for her three children or husband.

Two years ago, the Arellanos paid $269 a month to insure the family. The price jumped last year to $339 and this year to $780, more than their monthly mortgage payment.

Her husband works for a small landscaping company that does not offer insurance. So Mrs. Arellano is insured, but her husband, Jose, and their three children — Jackie, 16; Joe, 15; and Anthony, 13 — are going without insurance.

The Arellanos' income, which ranges from $2,800 to $3,200 a month, makes them ineligible for state-subsidized insurance. Their basic expenses run $2,000 a month or more.

"I'm one of those people in the middle," Mrs. Arellano said. "We don't make enough to pay for insurance ourselves, but we make too much to qualify for CHIP," the government-subsidized program for children.

So her children were recently at the Rockwall clinic for the physicals they need to participate in after-school sports, paying $25 instead of the $100 or more Mrs. Arellano would have paid at the doctor's office.

The family has catastrophic insurance, but Mrs. Arellano is uncertain how much longer she can afford it. Mr. Arellano's income typically drops in the winter, and his wife is hoping the children will then qualify for the state insurance program.

Even so, newly initiated regulations require families to reapply for the insurance every six months, rather than once a year, so they are not likely to qualify for long.

"I'll take what I can get," Mrs. Arellano said.