|

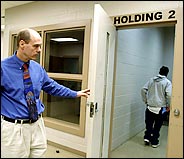

| Jeffrey Sauger for The New York Times |

| Fred Whitman, the intake officer at the Lucas County juvenile court in Toledo, Ohio, escorting a 12-year-old seventh grader into a holding cell. |

TOLEDO, Ohio The 14-year-old girl arrived at school here on Oct. 17 wearing a low-cut midriff top under an unbuttoned sweater. It was a clear violation of the dress code, and school officials gave her a bowling shirt to put on. She refused. Her mother came to the school with an oversize T-shirt. She refused to wear that, too.

"It was real ugly," said the girl, whose mother did not want her to be identified.

It was a standoff. So the city police officer assigned to the school handcuffed the girl, put her in a police car and took her to the detention center at the Lucas County juvenile courthouse. She was booked on a misdemeanor charge and placed in a holding cell for several hours, until her mother, a 34-year-old vending machine technician, got off work and picked her up.

She was one of more than two dozen students in Toledo who were arrested in school in October for offenses like being loud and disruptive, cursing at school officials, shouting at classmates and violating the dress code. They had all violated the city's safe school ordinance.

In cities and suburbs around the country, schools are increasingly sending students into the juvenile justice system for the sort of adolescent misbehavior that used to be handled by school administrators. In Toledo and many other places, the juvenile detention center has become an extension of the principal's office.

School officials say they have little choice. "The goal is not to put kids out, but to maintain classrooms free of disruptions that make it impossible for teachers to teach and kids to learn," said Jane Bruss, the spokeswoman for the Toledo public schools. "Would we like more alternatives? Yes, but everything has a cost associated with it."

Others, however, say the trend has gone too far.

"We're demonizing children," said James Ray, the administrative judge for the Lucas County juvenile court, who is concerned about the rise in school-related cases. There were 1,727 such cases in Lucas County in 2002, up from 1,237 in 2000.

Fred Whitman, the court's intake officer, said that only a handful of cases perhaps 2 percent were for serious incidents like assaulting a teacher or taking a gun to school. The vast majority, he said, involved unruly students.

In Ohio, Virginia, Kentucky and Florida, juvenile court judges are complaining that their courtrooms are at risk of being overwhelmed by student misconduct cases that should be handled in the schools.

Although few statistics are available, anecdotal evidence suggests that such cases are on the rise.

"Everybody agreed no matter what side of the system they're from that they are seeing increasing numbers of kids coming to court for school-based offenses," said Andy Block, who assisted in a 2001 study of Virginia's juvenile justice system by the American Bar Association's Juvenile Defender Center. "All the professionals in the court system were very resentful of this. They felt they were being handed problems and students that the schools were better equipped to address."

According to an analysis of school arrest data by the Advancement Project, a civil rights advocacy group in Washington, there were 2,345 juvenile arrests in 2001 in public schools in Miami-Dade County, Fla., nearly three times as many as in 1999. Sixty percent, the project said, were for "simple assaults" fights that did not involve weapons and "miscellaneous" charges, including disorderly conduct.

Many of the court cases around the country involve special-education students whose behavior is often related to their disabilities, Mr. Block and others say.

In an elementary school in northeastern Pennsylvania, an 8-year-old boy in a special-education class was charged with disorderly conduct this fall for his behavior in a time-out room: urinating on the floor, throwing his shoes at the ceiling and telling a teacher, "Kids rule."

"Teachers and school administrators know now that they can shift these kids into juvenile court," said Marsha Levick, legal director for the Juvenile Law Center of Philadelphia, which is representing the boy and has asked that the charges be dismissed. "The culture has shifted. Juvenile court is seen as an antidote for all sorts of behavior that in the past resulted in time out or suspension."

Experts say the growing criminalization of student misbehavior can be traced to the broad zero-tolerance policies states and local districts began enacting in the mid-1990's in response to a sharp increase in the number of juveniles committing homicides with guns, and to a series of school shootings.

While the juvenile homicide rate has since fallen, and many studies have found that school violence is rare, the public perception of schools and students as dangerous remains. Experts say zero-tolerance policies have created an atmosphere in which relatively minor student misconduct often leads to suspensions, expulsions and arrests.

"The idea that you try to find out why somebody did something or give a person a second chance or try to solve a problem in a way that's not punitive that's become almost quaint now," said Laurence Steinberg, a professor of psychology at Temple University and the director of the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Adolescent Development and Juvenile Justice.

What has also changed, Dr. Steinberg said, is that principals are less able to depend on parents to enforce the discipline schools mete out. "I think in the past the threat of getting in touch with a kid's parents was often enough to get a kid to start behaving," he said. "Now, kids feel parents will fight on their behalf."

In addition, Dr. Steinberg said, schools particularly urban schools with large numbers of poor children have been forced to reduce or eliminate mental health services. "In the past a lot of these kids would have been referred to specialists within the school or the school district. The juvenile justice system has become the dumping ground for poor minority kids with mental health and special-education problems."

The Toledo City Council passed the safe school ordinance in 1968 in response to concerns that schools had become dangerous. The ordinance allows for the filing of misdemeanor charges against students for anything from disrupting a class to assaulting a teacher. Juvenile court officials say relatively few students were charged with violating the ordinance before 1995, when Toledo police officers were assigned to secondary schools.

In 1993, only 314 charges were filed, according to Dan Pompa, the administrator for the Lucas County juvenile court. By 1997, he said, the number had more than tripled, to 1,111.

Arrests in the past year or so include two middle school boys whose crime was turning off the lights in the girls' bathroom and an 11-year-old girl who was arrested for "hiding out in the school and not going to class," according to the police report, which also noted, "The suspect continuously does not listen in class and disrupts the learning process of other students."

The girl's mother, who declined to be named, said, "I told them if she didn't want to go to school, put her in the detention center." The police took her daughter there in handcuffs, in the back of a police car.

Of the Toledo school district's 35,000 students, 47 percent are black, 43 percent white and 7 percent Hispanic. According to Mr. Pompa's figures, minorities account for about 65 percent of the safe school violations.

These higher rates are "something we would certainly want to keep an eye on," said Eugene Sanders, Toledo's schools superintendent.

Ms. Bruss, the schools spokeswoman, said it was the Toledo district's policy that students be charged with violating the ordinance only as a last resort. In addition, she said, most of those cases involve students with long histories of offenses.

Craig Cotner, chief academic officer for the Toledo public schools, said he believed part of the problem was that schools were being called upon to educate a far wider range of students than before. Thirty years ago, he said, students who were not performing well were counseled to drop out, and they easily found jobs at auto plants and other factories.

"For students who did not fit the mold whatever mold that may be there were many more options," Mr. Cotner said. "In some cases, those students who found it impossible to sit for five hours in a classroom could function very well in a labor environment." Today, he said, those students, with far fewer options, remain in school, but the school district has fewer resources to handle difficult students.

With a $15 million budget deficit last year, the district laid off 10 percent of the teaching force, or 231 teachers. Class size increased. With a $16 million deficit this year, more cuts must be made, Mr. Cotner said.

In addition, he said, a significant percentage of the district's resources must be used to fulfill federal mandates like the No Child Left Behind law, with its emphasis on accountability and testing.

Judge Ray of the county juvenile court says he sympathizes with school officials. "The schools have been called upon to fix everything that hasn't been working up to this point," he said. However, he said, juvenile court is not the appropriate place to solve adolescent problems.

Judge Ray has Mr. Whitman, the court's intake officer, and other court officers handle minor nonviolent offenses, offering counseling and referrals to the proper programs.

Mr. Whitman, 50, said he believed that no young person should ever be written off. "If a kid's not doing well, I think we need to sit down and find out what we can do to help him or her out," he said.

Mr. Whitman talked at length with the 14-year-old girl who had worn the midriff top and with her mother. "She didn't come across as a major problem at all," he said. "She knew the shirt was inappropriate. She just wanted to show off a certain image at the school. Probably she just copped an attitude. I expect that from a lot of girls."

An official of the girl's school said he could not discuss her case. He referred a reporter to the principal, who did not return calls to his office.

The girl's mother, who declined to be named, said she had not objected to the decision to arrest her daughter. "She wants to push authority to the hilt," she said.

The girl said of her encounter with school officials and the police: "I don't like to get yelled at for stupid stuff. So I talk back."