November 26, 2001

Bush's New Rules to Fight Terror Transform the Legal Landscape

By MATTHEW PURDY

|

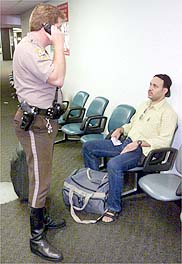

| (Reuters) |

| A Miami-Dade police officer, Darryl Crump, questioned an unidentified Kuwaiti man after he left a bag unattended at the airport on Sept. 13. He was allowed to leave. |

As Pentagon officials begin designing military tribunals for suspected terrorists, they are considering the possibility of trials on ships at sea or on United States installations, like the naval base in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. The proceedings promise to be swift and largely secret, with one military officer saying that the release of information might be limited to the barest facts, like the defendant's name and sentence. Transcripts of the proceedings, this officer said, could be kept from public view for years, perhaps decades.

The military tribunals are the boldest initiative in a series of laws and rewritten federal regulations that, taken together, have created an alternate system of justice in the aftermath of Sept. 11, giving the government far greater power to detain, investigate and prosecute people suspected of involvement in terrorism.

Those changes, described by legal experts and government and law enforcement officials, are likely to affect mostly residents of the country who are not citizens but who, until now, have had many of the constitutional rights and protections of citizens.

The Bush administration says its agenda commands strong public support, a view bolstered by recent polls. Even most critics acknowledge the need for enhanced security measures, but the administration's new approach has stirred unease both inside and outside government, as well as overseas.

Some senior law enforcement officials believe that the military tribunals are unnecessary and that the government's record in prosecuting terrorists in federal court over the last decade justifies continuing that approach. Spanish officials told the United States last week that they would not extradite eight men suspected of involvement in the Sept. 11 attacks without assurances that their cases would be kept in civilian court.

Although it remains unclear how widely these new powers will ultimately be applied, the provisions alter some basic principles of the American judicial system — like the right to a jury trial, the privacy of the attorney- client relationship and strong protections against the use of preventive detention.

The steps taken by the administration reflect outrage that the Sept. 11 terrorists were foreigners who lived freely and undetected in the United States, even though some had violated their visas, and the fear that potential terrorists or people with information about terrorist acts are among the millions of immigrants in the country.

"We're an open society, we give people access to the American dream," said Dan Bartlett, the White House communications director. "With that privilege there is a responsibility. That responsibility has not always been lived up to, and it's not always been asked that they live up to it, either."

President Bush's authorization of secret military tribunals for noncitizens accused of terrorism and the systematic interviewing of 5,000 young Middle Eastern men in the country on temporary visas is well known. But broad new powers are also contained in more obscure provisions.

A recent rule change published without announcement in the Federal Register gives the government wide latitude to keep noncitizens in detention even when an immigration judge has ordered them freed.

And under new laws, the attorney general can detain for deportation any noncitizen who he has "reasonable grounds to believe" is "engaged in any activity that endangers the national security of the United States," according to a recent internal Immigration and Naturalization Service memorandum.

Critics have said that the administration's measures often mean singling out people on the basis of nationality or ethnicity.

"We have decided to trade off the liberty of immigrants — particularly Arabs and Muslims — for the purported security of the majority," said David Cole, a law professor at Georgetown University who often represents detained foreigners.

In the guidelines for carrying out the 5,000 interviews with young Middle Eastern men, Attorney General John Ashcroft wrote to federal prosecutors that the selection of the men was not meant to imply "that one ethnic group or religious group is more prone to terrorism than another." Yet local law enforcement officials in several cities have balked at carrying out the interviews because of the impression of profiling.

Secrecy is a hallmark of the wartime judicial system, just as the free flow of information is a signature of the nation's normal criminal procedures. The names of about a dozen people being detained for months as material witnesses in the Sept. 11 investigation have been kept confidential because, officials explain, they are witnesses in grand jury proceedings. In ordinary cases, while grand jury proceedings are closed to the public, witnesses are rarely held in jail.

A full accounting of law enforcement activity related to the Sept. 11 investigation has not been made public. The Justice Department has not said precisely how many people are being detained, how many have been questioned and released and where people are being held and on what charges.

The new administration powers, amassed during wartime, have made the normally delicate balance between individual rights and collective security that much more precarious.

"My view on the military tribunals will be formed by how they're used," said Warren B. Rudman, the former Republican senator from New Hampshire and the chairman of the president's foreign intelligence advisory board. "If they're done carefully and with deliberation — and I really expect they will be — I don't have a problem with it."

"As far as ethnic profiling; it's very troubling. It pains me to say this, but some of it may have to be done. We just have to recognize that we cannot bend over backwards in our innate American fairness to overlook that there are some people trying to hurt us."

The Act: Bill With Long Name, and Longer Reach

The biggest changes in the government's power over residents who are not citizens were spelled out in a law known as the U.S.A. Patriot Act, hastily passed after the attacks. The measure's potential reach is summarized in the full name that was needed to create that acronym — the Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism Act of 2001.

Besides providing more money to strengthen border security, the act greatly expands the notion of who should be considered a terrorist and provides the attorney general with remarkable personal powers to detain such people.

In the past, entry into the United States was denied only to members of 28 groups that were formally designated as terrorist organizations by the State Department. But under the new law, any foreigner who publicly endorses terrorist activity, or belongs to a group that does, can be turned away at the border or deported.

The term "terrorist activity" has also been broadened to include any foreigner who uses "dangerous devices" or raises money for a terrorist group, whether or not he or she knows the group is engaged in terrorism. And perhaps most strikingly, the law allows the government to detain any foreigners whom the attorney general certifies as endangering national security.

The attorney general can order such detention if he simply has "reasonable grounds to believe" that the foreigner might be a threat. The Justice Department has to bring criminal or deportation charges against such people within seven days, but it can hold them indefinitely.

Mr. Ashcroft has said that such aggressive detention policies are "vital to preventing, disrupting or delaying new attacks. It is difficult for a person in jail or under detention to murder innocent people or to aid or abet in terrorism."

The administration has also changed rules to make it easier for officials to keep watch on both citizens and noncitizens while they are in federal custody. In one change, it has eased officials' ability to eavesdrop on communications between lawyers and their clients in federal custody when it would "deter future acts of violence or terrorism."

Defense lawyers say that new rule erodes a basic right of the accused to confer privately with their lawyers. But civil liberties lawyers have found more to object to in the wide provisions of the Patriot Act.

Noel Saleh, an immigration lawyer and vice president of the Arab Community Center for Economic and Social Services in Detroit, called the act "an extremely dangerous law in terms of the very expansive definition of the concept of terrorism. The consequences of being labeled a terrorist are extreme in that one can be detained indefinitely."

Mr. Saleh added, "That could theoretically happen to someone who at the end of Ramadan does their charitable tithing to an orphanage in South Lebanon that was established by Hezbollah."

Law enforcement officials have said they have not used the new powers yet because they already have enough authority to detain material witnesses and visa violators who have been picked up in the investigations.

The officials also said that many arrests of Middle Eastern men have been made not as a result of profiling but from a flood of tips pouring in about suspicious activities. And in many cases, the focus on Arabs and Muslims simply reflects the public's perception of where the current dangers lie.

Mr. Saleh said that since Sept. 11, the immigration service has held some of the detainees longer than usual by opposing their release on bail, forcing them to appeal to judges for bonds, a process that can add three to four weeks to their time in jail.

"I obviously think that this is improper," said Mr. Saleh, who represents six Middle Eastern clients detained in the recent investigations. "It's an abuse of discretion." Still, Mr. Saleh said he would not complain about what others see as selective enforcement, because clamping down on visa violators is what the immigration service is "supposed to do."

And if anything, some law enforcement officials say, the agency has been too timid. Conscious of the concerns about racial profiling, the agency has been reluctant to cull its files for people who have overstayed their visas, and it has generally detained only those Middle Easterners who have been of interest to the F.B.I.

It also has begun to turn back some visitors who once would have passed easily into the country.

At the F.B.I.'s prodding, in mid-October, the immigration service refused entry at Kennedy International Airport in New York to a Jordanian who is an official of the Palestine Liberation Organization, law enforcement officials said. They said the man was on his way from Cairo to Los Angeles to do something that suddenly seemed a little worrisome: he was planning to attend flight school. He was put back on a plane to Cairo.

The Tribunals: Swift, Secret Justice, and No Appeals

At the Pentagon, very little has been disclosed regarding the shape of the military tribunals that President Bush has ordered, but one thing is clear: they will be unlike any judicial proceedings in this country since the end of World War II.

Suspected terrorists will be tried not before a jury but rather a commission made up primarily — though not necessarily exclusively — of military officers. The suspects and their lawyers, who may also be military officers appointed to represent them, will be tried without the same access to the evidence against them that defendants in civilian trials have. The evidence of their guilt does not have to meet the familiar standard "beyond reasonable doubt" but must simply "have probative value to a reasonable person."

There will be no appeals.

"The commission itself is going to be unique," said one military officer involved in the discussions. "It will be separate and distinct from a civilian criminal trial. It will be separate and distinct from a court-martial."

Mr. Bush's order establishing the tribunals — issued on Nov. 13 not as an executive order but rather as a military order by the president in his constitutional capacity as commander in chief of the armed forces — set only broad guidelines for the tribunals. It said, for example, that convictions and sentences could be reached by only a two-thirds vote of the commission's members. It also left to Mr. Bush himself the decision on who would face prosecution in the tribunals.

The rest of the details — the rules of evidence, the composition of the tribunals, the forums to be used — are now being debated inside the Pentagon.

Secretary of Defense Donald H. Rumsfeld said that he had ordered the Pentagon's civilian general counsel, William J. Haynes 2nd, to begin drafting the procedures.

"The president's order is not terribly specific," one senior officer said. "Who prosecutes? Who defends? All of those things are up for grabs right now."

So far no one has been brought up before a tribunal, though some administration and Pentagon officials said it could happen soon. Officials are debating whether to prosecute Zacarias Moussaoui, 33, a French citizen of Moroccan descent being held in New York, through the tribunal process.

Mr. Bush's aides justified his decision by citing similar tribunals held throughout American history, from the Revolution through the Civil War and international tribunals in Nuremberg after World War II.

Mr. Bush's decision has provoked criticism from across the political spectrum, but legal experts are divided over the tribunals.

Phillip Allen Lacovara, a former deputy solicitor general, said military tribunals promised a more proportional prosecution of what, in the case of the attacks of Sept. 11, amounted to crimes of war than any criminal trial in a civilian court could.

Some federal law enforcement officials questioned the need for tribunals, given the government's success at convicting terrorists in civilian courts. But Mr. Lacovara noted the length of those prosecutions, including the trials of some of those charged in the 1993 World Trade Center bombing. He said the Bush administration was almost certainly considering the greater feasibility in a military tribunal of imposing the death penalty.

"People charged with violations of the laws of war are not entitled to the same level of guarantees as civilians charged with crimes," he said, citing Supreme Court rulings that have upheld the tribunals in the past, "as long as the proceedings are fundamentally fair."

The Reasoning: Trails Lead to Middle Easterners

The White House insists that the new emphasis on preventing terrorist attacks has not led to racial profiling — a practice that has become increasingly discredited in recent years with disclosures that the state police in New Jersey and elsewhere had pulled over disproportionate numbers of black men.

In the weeks since Sept. 11, said Mr. Bartlett, the White House communications director, investigators have simply followed the tips and evidence they had. "The idea was not that we were going to find all visa violators from the Middle East," he said. "That may have been the result."

But some law enforcement officials acknowledge that they have focused extra attention on young men whose last names suggest Middle Eastern origins. Just last month, detectives in New York City's warrants division culled through the police department's computers for people with Middle Eastern names for whom there were outstanding arrest warrants for petty crimes. Nearly 100 people were picked up and questioned about terrorism, an investigator said, with the warrants used to encourage full cooperation.

The federal government has conducted its own, wide-ranging interview program. In recent days, investigators have begun conducting "voluntary" interviews with 5,000 young Middle Eastern men who have entered the United States in the past two years from countries with links to terrorism.

The interviews are voluntary because under the Fourth Amendment, an involuntary detention for questioning might well be a "seizure" requiring justification, at a minimum, on the basis of some reason to suspect a particular individual of a particular crime.

The federal investigators are looking for evidence that they do not yet have, evidence that might shed light on the terrorist network that planned the Sept. 11 attacks or that might still be in the process of planning others.

On more than 200 college campuses federal investigators have contacted administrators to collect information about students from Middle Eastern countries: what they are studying, where they are living, how they are doing. The investigators are also paying unannounced visits on the students themselves, asking anything from their views on Osama bin Laden to their educational plans.

Unlike the actual detention of hundreds of Arab men, these investigatory sweeps have aroused little public controversy or criticism — with one exception. Some police chiefs, having worked hard to put racial profiling to rest, have said they would not cooperate with the F.B.I. because the sweep appears to violate departmental policy or state or local laws against racial profiling or intelligence gathering for political purposes.

Walter E. Dellinger, acting solicitor general in the Clinton administration, said he had qualms about measures that applied to select groups of people.

"I am more willing to entertain restrictions that affect all of us — like identity cards and more intrusive X-ray procedures at airports — and somewhat more skeptical of restrictions that only affect some of us, like those that focus on immigrants or single out people by nationality," he said.

But Mr. Dellinger said infiltration and surveillance were necessary to combat terrorists. "We're going to find it impossible to physically protect every location," he said, "so we have to take significant steps that lead to a new level of intrusion."

Copyright 2001 The New York Times Company

![]()