February 11, 2002

Cleveland Case Poses New Test for Vouchers

By JACQUES STEINBERG

|

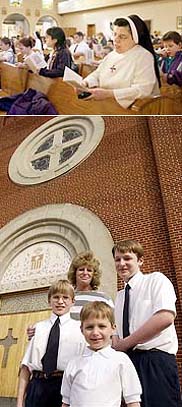

| (David Maxwell for The New York Times) |

| St. Rocco's Roman Catholic School in Cleveland, where Sister Judith Wulk, top, is principal, benefits from an Ohio voucher plan. The plan helps Kendall Stefanowicz, above, whose sons attend the school. |

CLEVELAND, Feb. 7 — The other afternoon at St. Rocco School on this city's gritty west side, the first graders in one classroom were reading aloud from a book about the four food groups while the fifth graders down the hall were rattling off the economic attractions of various American cities.

That they did so under the portraits of Jesus and the Virgin Mary, on a day in which all of them would be required to pray at Mass, was not unusual for a Roman Catholic school in the United States.

But what distinguishes St. Rocco from Catholic schools in other parts of the country is that the State of Ohio is paying the bulk of the tuition for half of the school's 200 pupils, who are the recipients of vouchers designed to help them and several thousand other children in Cleveland flee failing public schools.

The question of whether such an arrangement amounts to outright government aid to parochial schools and thus violates the Constitution's separation of church and state will be taken up by the United States Supreme Court this month. The justices are scheduled to hear oral arguments on Feb. 20 on the legality of the state's six-year-old tuition voucher program, which is open only to parents in Cleveland, where barely a third of public school students graduate from high school.

A complicating factor that the justices may well consider is this: Many of the pupils who receive the tuition assistance were already attending parochial or other private schools, raising questions about whether the program is ending up assisting parents who had already found the ways and means to educate their children outside the public schools.

In the current school year, the state has awarded publicly financed vouchers, worth as much as $2,250, to 4,456 students in kindergarten through eighth grade, mostly from families living at or below the poverty low. Each is permitted to attend 1 of 50 private schools that has agreed to accept them. Like St. Rocco, nearly all of those participating schools are affiliated with the Catholic church or other religious groups. Fewer than 1 percent of the pupils in the program are in nonreligious private school.

In a voucher program in Milwaukee, a third of the 10,000 participants are enrolled in nonreligious private schools. So the Cleveland case, by contrast, provides the court with the opportunity to make an unambiguous statement about the constitutionality of a state-financed program that funnels nearly all of its money, through parents, to religious schools.

The court will be hearing Ohio's appeal of a decision by the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, which found that the program was unconstitutional, ruling that it had the "impermissible effect of promoting sectarian schools." Several years ago, the Supreme Court declined to hear a challenge to the Milwaukee program.

An endorsement of the Ohio program by the Supreme Court could prompt other states and cities, and perhaps the Bush administration, to consider following the lead of Cleveland, Milwaukee and Florida, which has initiated a similar pilot program.

A negative ruling, if broad enough, could effectively silence the private- school wing of the so-called school choice movement. Voucher advocates have had to rely primarily on religious institutions because such schools are usually among the few with tuition low enough to have an incentive to accept the vouchers, which may still be less than what the school normally charges.

"If you look at the voucher conversations that have taken place to date, the constitutional ambiguity has served as a deterrent for states to go the voucher route," said Eric Hirsch, an education analyst at the National Conference of State Legislatures, a nonpartisan organization with no position on such programs. "This case, in clearing up some of these problems, could lead to potential passage of legislation in this area."

But the Cleveland case also gives the court an opportunity to explore whether the Ohio voucher program is succeeding in meeting what supporters here and elsewhere cite as its primary mission: to provide an escape route for low-income pupils, especially blacks, mired in an inner- city public school system that is among the lowest-rated in the nation.

Many of the Cleveland families receiving vouchers, which are distributed via lottery, are indeed poor, with a median income of about $20,000 annually. But an analysis by a private group found that at least 33 percent of the pupils who received the vouchers here in the last school year were already enrolled in parochial or other private schools, and thus had never intended to go to public schools, let alone transfer out of them with the state's help.

While half of the students who participate in the voucher program are black, the proportion of students in the public school system who are black is closer to three quarters, according to state records, suggesting that blacks may not be applying in numbers proportionate to their school population. Whites, by contrast, apply for the program in numbers that are almost double their representation in the public school population, the records show.

State officials said that they had no firm figure on the total number of parents who applied for vouchers, because some who received them ultimately gave them back and others who were initially rejected were encouraged to apply again.

At St. Rocco, nearly every family that secured a voucher was already sending its school-age children to the school. And more than half of those families were white. Among the recipients is Kendall Stefanowicz, 39, who has three sons at St. Rocco and who said that without her three vouchers she would have had to get a job to supplement the income of her husband, a truck mechanic.

"I can stay home with my kids," said Mrs. Stefanowicz, explaining that her husband's income was less than $50,000 a year. "I can do homework with them. I don't have to be stressed out."

Opponents of vouchers say that Mrs. Stefanowicz's rationale for accepting the state's help — echoed by other parents at the school — is a diversion of the program's primary aim and suggests that parents who benefit are those who would have been sending their children to religious schools without the aid. St. Rocco's, like other religious schools, encourages the parents of current students to apply for the program.

"It is not accomplishing the goal that is most often ascribed to it by proponents," said Zach Schiller, a senior researcher at Policy Matters Ohio, the nonprofit organization that analyzed the school histories of the voucher participants, and which counts at least one voucher opponent on its board. "It is not serving largely as a way for inner-city African- American students to leave the public school system."

Supporters of the program disagree. They point to statistics, also compiled by Policy Matters Ohio, which suggest that 46 percent of the students who receive vouchers do so on entering kindergarten, and many of them may have ended up in public school had the program not existed.

"At some point, these parents made a fundamental choice," said Joseph P. Viteritti, a professor of public policy at New York University and the author of a 1999 book, "Choosing Equality" (Brookings), which supports vouchers for low-income students. "The question is, should they be burdened financially because they made that choice?"

Professor Viteritti and other voucher proponents also argue that while 99 percent of the voucher recipients in Cleveland attend a religious school, the program was not designed to engineer that result.

In the program's first year, in 1996, about a quarter of the recipients attended nonreligious private schools. But in the years since, several of those schools either went out of business or became charter schools, which are public and receive more money per pupil from the state than if they were schools in the voucher program. While the state invited suburban public schools to accept the voucher students, none agreed to do so.

In the end, voucher parents say, they should be entitled to direct part of their taxes to a school of their choosing, whether public or private.

"It's basically a G.I. Bill for kids," said Clint Bolick, vice president of the Institute for Justice, a public- interest law firm that has defended the Cleveland, Milwaukee and Florida programs. "Not a single dollar crosses the threshold of a religious school until a parent chooses not to avail himself or herself of a public education."

Copyright 2002 The New York Times Company

![]()