|

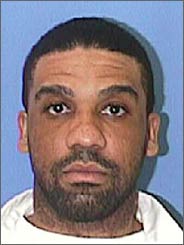

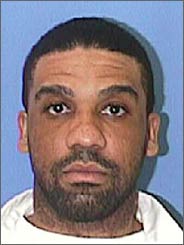

HOUSTON, — Napoleon Beazley, 26, of Texas, and Christopher Simmons, 26, of Missouri, both committed murder when they were 17. They filed identical claims before federal and state courts, arguing that executing an inmate who was younger than 18 at the time of his crime violates the Eighth Amendment's provision against cruel and unusual punishment.

Today the Missouri Supreme Court granted Mr. Simmons, who was to be executed next week, a stay pending the outcome of a related United States Supreme Court case that will be decided by the end of June. Mr. Beazley was put to death by lethal injection in Huntsville shortly after 6 p.m. after the United States Supreme Court refused to hear his petition and the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals denied his motion for a stay, and after the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles voted 10 to 7 against clemency.

Gov. Rick Perry accepted the board's recommendation and denied Mr. Beazley's request for a 30-day reprieve. "To delay his punishment would be to delay justice," the governor said in a statement shortly before Mr. Beazley's execution.

Mr. Beazley shot John Luttig, 63, the father of a federal judge, in a botched carjacking in 1994. Mr. Luttig's daughter, Suzanne Luttig, watched the execution in Huntsville but did not speak to reporters.

Mr. Beazley, who had been his high school senior class president and a football star in Grapeland, Tex., apologized today in a handwritten statement for a murder that was "not just heinous, it was senseless."

Paddy Burwell, one of the board members who voted to commute Mr. Beazley's punishment to a life sentence, was working on his ranch, between San Antonio and Victoria, when he learned that Mr. Beazley had been executed. "I'm really apprehensive that this is a day we're going to be sorry about for a long time," Mr. Burwell said in a telephone interview. "I just feel like something really wrong has happened."

The pending United States Supreme Court case is expected to decide whether there is now a "national consensus" that executing the mentally retarded constitutes cruel and unusual punishment. Lawyers for both Mr. Beazley and Mr. Simmons, as well as other legal experts, said that if the court outlaws the execution of the mentally retarded, the ruling could also undermine the opinion that allows the execution of inmates who committed capital murder when they were younger than 18.

The decisions made today by courts and officials in Missouri and Texas show "how incredibly arbitrary the death penalty system is," said Elisabeth Semel, the director of the death penalty clinic of the Boalt School of Law at the University of California at Berkeley.

"Missouri looks to the Supreme Court and is apparently concerned that a decision is imminent that may have implications for the execution of Christopher Simmons," Ms. Semel said. "So it says stop. But Texas goes ahead."

The Texas pardons board's vote of 10 to 7 against clemency — in the form of a commutation to a life sentence — was a slim margin in a state where the overwhelming majority of the board votes since 1996 have been unanimous in favor of execution.

Brendolyn Rogers-Johnson, 52, is a board member who also voted for clemency. "I weighed all the information and agonized over it and dreamt about it and thought about it," she said in a telephone interview.

Ms. Rogers-Johnson, a former high school English teacher, said that a number of factors had influenced her decision, including Mr. Beazley's age at the time of the crime and the fact that he had no prior criminal record. "There was a strong possibility that he would not be a danger," she said.

To win a death sentence for Mr. Beazley, prosecutors had to prove his "future dangerousness," a difficult task considering his age and his lack of a record, but one helped greatly by the testimony from the two brothers who were his co-defendants. One of them, Donald Coleman, testified that before the killing Mr. Beazley had talked about "wanting to hurt someone" and that he said he wanted "to see what it feels like to see somebody die." Mr. Coleman later recanted his testimony, saying it was part of a deal with prosecutors to avoid the death penalty, but prosecutors deny that.

The Smith County district attorney, Jack Skeen, Jr., who prosecuted the Beazley case, and Ed Marty, an assistant district attorney who handled the appeals, were present at the execution today. But both refused to talk to reporters.

![]()