| Gary Mark Gilmore |

Executed January 17, 1977 by Firing Squad in Utah

1st murderer executed in U.S. in 1977

1st murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

1st murderer executed in Utah in 1977

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence | ||||

| Gary Mark Gilmore W / M / 25 - 26 |

Max David Jensen W / M / ? Ben Bushnell W / M / 25 |

Summary:

On Monday, July 19, 1976, Max Jensen went to work as usual at the self-service gas station in Orem, Utah. That night, Gilmore had a spat with his girlfriend and went driving with her mentally unstable younger sister, April. At around 10:30 pm he told April he wanted to make a phone call. He left her in the truck and walked away. Gilmore went around the corner, out of her sight, and into the Sinclair service station. He spotted the attendant and quickly saw that no one else was around. He walked up to Max Jensen and pulled out a .22 Browning Automatic. He instructed Jensen to empty his pockets, which the young Mormon quickly did. Then he told Jensen to go into the bathroom and lie down on the floor with his arms under his body. Jensen got into the position. He was obeying everything that Gilmore said. Then inexplicably, Gilmore put the gun close to Jensen's head. "This one is for me," he said, and fired. Then he placed the muzzle right against Jensen's skull and shot him once again, this time "for Nicole." (girlfriend Nicole Baker Barrett)

Gilmore spent the night with April at a motel and the following night, he walked into the City Center Motel in Provo, not far from Brigham Young University. He confronted the attendant, Ben Bushnell, who lived on the premises with his wife and baby. Gilmore told Ben to give him the cash box and get down on the floor. Then he shot Bushnell in the head. Bushnell's wife came in, so Gilmore grabbed the cash box and left. Trying to dispose of the gun in a nearby bush, Gilmore shot himself in the hand. By Wednesday, Gilmore's cousin, Brenda Nicol, turned him into the police. Gilmore gave up near a roadblock without a fight. At first, he denied the murders, but later admitted both.

In October, Gilmore was tried, convicted, and sentenced to death. He chose death by firing squad and waived all appeals. Despite the efforts of other groups to stop it, 6 months after the murders, the execution was carried out. Gary Gilmore was the first person executed in the U.S. in almost 10 years. In prison most of his life and paroled only four months before the murders, Gilmore becomes a celebrity with his efforts to hasten his execution. His last words: "Let's do it."

Citations:

Gilmore v. Utah, 97 S.Ct. 436 (1976).

Internet Sources:

The Crime Library

"Gary Gilmore: Death Wish," by Katherine Ramsland.

Freedom

It's not that his ambitions were great that got him into trouble, but that he hadn't the patience to earn what he desired. From a young age, Gary Mark Gilmore just went out and took whatever he wanted — beer, cigarettes, cars, money. More times than not (according to him) he was successful, but when he wasn't, he landed in the slammer. He'd just get an idea into his head and do it. He said he couldn't help himself.

Gilmore's story is documented in a book written by his younger brother, Mikal Gilmore, called Shot in the Heart, and by Norman Mailer, who wrote a narrative nonfiction account, The Executioner's Song, in which he utilized letters that Gilmore wrote, interviews with many of his intimates, trial transcripts, and interviews or statements that Gilmore gave to the press. Mailer did not himself interview Gilmore, but his account relies on actual documents, with an emphasis on how those around Gilmore perceived him. There are also a few film clips available of Gilmore as he spoke to the press or to the courts, and an A&E documentary collected these into an overview of his fight to die rather then face years in prison. Gilmore is a historical case, in that he was the first man to be executed after the U. S. Supreme Court reinstated the death penalty, and because he refused all appeals to which he was legally entitled.

Born on December 4, 1940, he'd aspired as a boy to become a man of God. By the time he was thirty-five, he'd spent more than half of his life in prison, from juvenile detention to a federal penitentiary. At age 14, he dropped out of school. By fifteen, he was running an illegal car theft ring. That's when he was first arrested, although he'd been drinking for three years, harassing teachers, playing hooky, and stealing petty items. According to his own statements to court-ordered psychologists, he developed a need for bravado, which meant staring down approaching trains until near-impact or sticking a wet finger into an outlet.

Upon his first arrest, his father Frank got a lawyer and got him off, teaching him to manipulate the legal system and skirt responsibility for criminal acts. After all, Frank had made a living at it for many years. He was a professional con man, but could not abide the taint of criminality in his son.

However, Gilmore then stole something that got him into Oregon's MacLaren Reform School for Boys. He spent a year there, and then went in and out of jail until he was eighteen. At that point, he ended up in the Oregon State Correctional Institution on a car theft charge. His father couldn't do much for him, especially after he piled up an array of disciplinary charges while in prison. Then he was out and then in again, and this time while he was behind bars, Frank Gilmore died. According to statements made by one of the wardens in the documentary, "A Fight to Die," Gary went wild, tearing up his cell and attempting suicide. This was a blow he could not bear.

Yet there was no release for him, no respite to mourn. He became violent to guards and inmates alike. Because he was so difficult to handle, he was heavily drugged with an anti-psychotic called Prolixin, and only with his mother's horrified intervention was he removed from this dehumanizing regimen. He never forgot its paralyzing effects. He got out when he was 21 and promptly committed robbery and assault for $11. At this point, the State of Oregon decided that he was a repeat offender with a poor prognosis. He went to Oregon State Penitentiary. While incarcerated, his brother Gaylen, the third of Bessie and Frank's four boys, was stabbed in the stomach. Mikal Gilmore documents this tragic incident. Having no money for medical care, Gaylen died. This time, Gary was allowed to attend the funeral, but losing Gaylen had its effect. Gary often ended up in solitary confinement over his inability to conform to the prison routines.

Yet spending so much time alone in solitary proved beneficial. With an IQ of 130, he educated himself in literature and began to write poetry. More notably, he developed an artistic talent that won contests. For that, he was granted an early release in 1972 to live in a halfway house in Eugene and attend art school at the local community college. While he welcomed this opportunity, it apparently intimidated him. Rather than show up to register, he stayed away and drank. He visited his brother Mikal, who reported that he was afraid of Gary. Within a month, Gilmore had committed armed robbery and was arrested. When he went to trial again, he asked permission to address the court, which was granted, and his actual words are recorded in several places, including court transcripts.

With great articulation, Gilmore made an appeal for leniency. He said that he had been locked up for the past nine and a half years, with only two years of freedom since he was fourteen. Justice had been harsh and he'd never asked for a break until now. He argued that "you can keep a person locked up too long" and that "there is an appropriate time to release somebody or to give them a break. ...I stagnated in prison a long time and I have wasted most of my life. I want freedom and I realize that the only way to get it is to quit breaking the law. ...I've got problems and if you sentence me to additional time, I'm going to compound them."

The judge told him that he had already been convicted once for armed robbery, a serious charge, so there was no option but to sentence him to another nine years. Gilmore was hurt and angry. As promised, he became more violent while in prison and on a number of occasions tried unsuccessfully to kill himself. They wanted to try Prolixin again, but Gilmore begged for an alternative. He was transferred to a maximum-security penitentiary in Marion, Illinois. That meant that no one in his family could visit him. He started writing to a cousin in Utah, Brenda Nicol, and only three years into his sentence, a parole plan was worked out. Brenda gave several interviews about her involvement with Gary, and Mailer offers a complete description of her account.

Brenda orchestrated Gilmore's release. She hadn't seen Gary since he was a boy, but she remembered how distinctive he was. She believed that if she and her family could help him out with a loving community and a job, he'd get along okay. She didn't know that he'd been diagnosed (according the reports that Mailer documents) with a psychopathic personality disorder. She had no idea how compulsive he was, or demanding. It was in her mind to do a good deed, so she worked on bringing Gary home. Finally in 1977, he was released to go live in Provo. He arrived with everything he owned packed in a small gym bag. He was ready for freedom, he firmly believed.

Yet life in Utah proved to be hard. He'd hated prison, but the skills he'd developed there to survive just didn't work in a conservative Mormon community. He was briefly employed in his Uncle Vern Damico's shoe shop and then did insulation for a man named Spencer McGrath, but he had a hard time concentrating. The first chance he got, according to interviews that Vern Damico gave to Mailer, he went out drinking. When he couldn't afford beer, he stole it. Then he found himself a beautiful girlfriend, Nicole Baker Barrett, thrice divorced by age 19, and soon returned to a life of compulsive theft because he wanted what he wanted ... right now.

It was the sight of a white Ford pickup truck priced well beyond his means that appeared to those who knew him to have sparked a spree that could only have ended badly.

First Victim

Gilmore had bought a blue Mustang from Val Conlin, a used car dealer, but it had problems and often wouldn't run. He still owed on that but he'd seen a ten-year-old, overpriced white truck on the lot that he really wanted. The dealer said no way, not unless he found himself a co-signer. That frustrated Gilmore. By hook or by crook, he intended to have that truck.

To his mind, there were always ways of getting money. He'd already stolen some merchandise to sell. Then he managed to collect a bag full of guns---nine of them. He gave one to Nicole, she later told police officers, showed her the rest, and said he intended to sell whatever he could. Nicole's interview for A&E is the best source of information for what happened in those final days, along with Gilmore's own documented admissions. Each person who saw him over the next few days later gave interviews on film as well. Gilmore had scared her. He'd already shown a violent side, she later related, and now this. She didn't know what to do.

Gilmore had moved into her rented home in Spanish Fork, near Provo, but things weren't always so good. He often took a drug, Fiorinal, for headaches and he drank all the time, which created sexual dysfunction, an inability to think clearly, and a great deal of frustrated anger. He was impulsive and demanding, and there were times when Nicole was actually afraid of him, though she loved him. Once when he'd picked her up she'd had the feeling of an evil presence emanating from him. She thought he might be the devil, and there were times when he acted like he was. He even claimed he knew Charles Manson. Finally it all just got to her. She just took her two children and went to live in an apartment five miles away.

Gary went looking for her. He was in a state. She wasn't going to run out on him. He told his cousin Brenda he might just kill her. But he couldn't find her. On top of that, he was now deeply in debt with no clear way out ...except the only way he knew. He'd been free less than three months and already he couldn't cope.

Mailer interviewed the families of Gilmore's victim's and Gilmore's friends to put together the following accounts:

On Monday, July 19, 1976, Max Jensen went to work as usual at the self-service gas station in Orem, Utah. His shift went from 3 in the afternoon until 11. He was just there until he could find a job that paid more so that he and his new wife could get a little security.

At around the same time that Max was going through the routines of his job, Gilmore learned that no one would co-sign on the truck for him, so he insisted that he himself could pay it off within a few weeks. Conlin assured Gilmore that he would repossess the truck at once if the payments weren't made. Then Gilmore left with the truck and headed toward Nicole's mother's house. Nicole wasn't there, but her mentally unstable younger sister, April, had a crush on Gary and was happy to go for a ride in his new truck. She told him she wanted to stay out all night. Angry and hurt by Nicole, as he later said in letters to her, he was pleased to oblige.

Around 10:30 that evening, he told April he wanted to make a phone call. He left her in the truck and walked away. She had no idea where he was going.

Gilmore went around the corner, out of her sight, and into the Sinclair service station. He spotted the attendant and quickly saw that no one else was around. He walked up to the man, whose nameplate read "Max Jensen" and pulled out a .22 Browning Automatic. He instructed Jensen to empty his pockets, which the young Mormon quickly did. Then he told Jensen to go into the bathroom and lie down on the floor with his arms under his body. Jensen got into the position. He was obeying everything that Gilmore said.

Then inexplicably, Gilmore put the gun close to Jensen's head. "This one is for me," he said, and fired. Then he placed the muzzle right against Jensen's skull and shot him once again, this time "for Nicole."

To his surprise, the blood spread fast and got on his pants. He turned around and left the gas station, not even noticing the wad of cash on the counter.

His next move was to take April to see a movie, "One Flew over the Cuckoo's Nest." Then they went over to Brenda's. She thought Gilmore was strangely agitated. He had some clothes that he didn't seem to want her to see. He didn't stay long and she couldn't get over the feeling that something was up.

Without further explanation, Gary drove off with April and they got a room at a Holiday Inn. While they slept, the hunt began for Max Jensen's killer. Around 11:00 p.m., a customer had found the body.

The Killing Continues

Ben Bushnell, 25, was the manager of the City Center Motel in Provo, not far from Brigham Young University. He and his wife lived on the premises with their infant son, and things looked promising for Ben's future.

On Tuesday July 20, Gilmore had trouble with his new truck, so he took it to gas station three blocks from his Uncle Vern's house. Upon learning that a fix could take twenty minutes, according to Norman Fulmer, the man who ran the gas station, Gilmore decided to run a little errand. He walked down the street and saw the City Center Motel next to Uncle Vern's. Emboldened by his previous murder, he got an idea. He went into the lobby.

Ben had just come in from the store so he asked Gilmore what he wanted. Gary told Ben to give him the cash box and get down on the floor. Then he shot Bushnell in the head. But the man wasn't dead yet. He lay there twitching and trying to move. Gilmore wasn't sure what to do, but just then Bushnell's wife, Debbie, came out so Gilmore grabbed the cash box and left. He pocketed the cash and placed the box under a bush. A block later, he took the gun he'd used by the muzzle and shoved it into another bush, but something caught the trigger and he took a bullet in the fleshy part of his hand, between the thumb and palm. He went into the garage to get his truck and the owner, Norman Fulmer, spotted the trail of blood. Then on the police scanner Fulmer heard about an assault and robbery at a nearby hotel. He wrote down the truck's license plate number and after Gilmore drove away, Fulmer called it in. Patrol cars sped through town and SWAT teams turned out to track and capture Gilmore. They figured he'd just killed a man for around $125. Pretty much like the murder in Orem the night before.

Uncle Vern came out to see what all the excitement was about, and it wasn't long before he realized that his nephew was involved. Over the past month, he'd watched Gilmore go from bad to worse, especially when he drank, and this brutal act seemed to cap his latest escalation of acting out. Vern's wife called Brenda, and she in turn called a police dispatcher she knew. Then Gilmore called her. He admitted he'd been shot and needed help. He told her where he was. Brenda sent the police to go get him. About the same time that they were evacuating neighbors and closing in, Debbie Bushnell was learning that the paramedics couldn't save her husband. He was dead.

Afraid that Brenda wasn't coming, Gilmore left the house where he'd gotten some first aid and drove right through a police roadblock. Then it dawned on the cops that he was the guy. They set out after him and eventually ordered him to stop just outside Nicole's mother's house. Gilmore gave up without a fight. He asked only that they be careful of his wounded hand.

Nicole was there. She went out and saw him lying on the ground. Then she overheard the cops suggest that he'd just committed two murders. She couldn't help but wonder if her leaving him had something to do with it, but she also though he was one stupid, crazy son-of-a-bitch.

Brenda soon learned that no one else had been hurt and Gilmore was now in custody. She knew he'd hate her for it, and when he asked her the next day why she had turned him in, she said, "You commit a murder Monday, and commit a murder Tuesday. I wasn't waiting for Wednesday to roll around." (This is her recollection as she recounted it to both Mailer and the A&E crew.)

While Gilmore eventually accepted the fact that what he'd done was wrong and he deserved to be punished, he never totally forgave her for this betrayal. When she turned him in, she had effectively separated him forever from Nicole. To his mind, she could have driven him to the border and let him go up to Oregon. He didn't seem to get it.

Upon his arrest, Gary said that he'd talk with one cop, Gerald Nielsen, and he freely spoke about his various interactions with Gilmore in film and to Mailer. At the hospital, a test on Gilmore's hand indicated that he'd recently held metal in it. Then it was set in a cast.

Nielsen then tried to get him to admit to the murders. He said that he had not killed anyone and that he could account for his whereabouts. He even said there were witnesses who would vouch for him. The facts were, as he recounted them, that he'd come across a guy holding up the man at the motel. He tried to stop it and got shot in the hand for his trouble. On the night before, he'd been with April the whole night and she'd be able to tell them that he hadn't killed anyone.

The story didn't check out; it was full of holes. In fact, there was a witness who had seen Gilmore with the gun and the cash box at the motel. April knew that Gilmore had left her to "make a phone call." Then Val Conlin found Gilmore's stash of stolen guns. He called the police and turned them in. Nielsen went back to try again. This time Gary simply said he didn't know why he had killed the two Mormons. He didn't have a reason. He admitted that if he hadn't been caught, he'd likely have gone on killing. Not much later, he said that he ought to die for what he'd done.

On August 3, at the preliminary hearing, prosecutor Noall Wootton met Gilmore for the first time. Mailer indicates from interviews that Wootton was impressed with the prisoner's intelligence, and it struck him that this man embodied the system's utter failure to rehabilitate. Gilmore would never be anything but dangerous---yet he might have been so much better than that.

For the next few months, Gilmore and Nicole wrote love letters to each other with great intensity, sometimes three a day. She knew that he faced life in prison, and possibly worse, yet she couldn't unhook herself from this enigmatic man who'd walked into her life and changed it forever. They swore an eternal bond. By October, everything was ready for trial. Since the case for the Bushnell murder was the strongest, the prosecution concentrated on it. If need be, they could go back and try Gilmore for Jensen's murder, but Wootton expected to prove his case. He had plenty of witnesses, even without the questionable confession. If Harry Houdini was really Gary Gilmore's grandfather, as his mother had often intimated, perhaps he'd passed down a few tricks on getting out of hopeless situations. Gilmore would need them.

Destined For Death

How does someone with talent and intelligence fall into such a life? Why would Gary Mark Gilmore develop into a habitual criminal who so thoughtlessly took the lives of two young men who'd done nothing to him? In his case, the answer seems to lie with the turbulent family in which he'd grown up; it had been full of fantasy and denial, coupled with rampant and random abuse. Years later, Gary's youngest brother, Mikal, researched their family's history for his book, Shot in the Heart, to see where things went wrong. His feeling was that Gary reminded their father of his own failings in life and therefore got the brunt of the man's anger. Gary's conduct disorders as a juvenile, coupled with his compulsive personality, took the path of least resistance ---straight into the narcissistic and remorseless depths of psychopathy. He never knew when he'd get beaten, nor why, so he formed a notion of a harsh and punitive reality that made no sense. In many ways, the prison system itself was a metaphor of his father. No matter how he resisted and reacted, he'd always get beat up.

Frank Gilmore Sr. was a con man and an alcoholic. He'd married Bessie on a whim, and he'd had many wives and families before her, none of whom he cared about or supported. They had a son, Frank Jr., and then Gary came along while they were wandering aimlessly through Texas under the pseudonym of Coffman to avoid the law. Frank christened him Faye Robert Coffman, which Bessie quickly changed to Gary, but this birth certificate proved to be a sore spot years later. Gary thought he'd been illegitimate, deciding that this was the reason that his father had never loved him.

Frank had many dark secrets and Bessie was a Mormon outcast. They seemed to cling to each other to escape the realities of their pathetic lives. Frank craved independence and would disappear for long stretches of time. Bessie, for her part, did not allow the children to touch or hug her, so there was emotional deprivation from both parents. Yet Bessie did want security, so she persuaded Frank to settle in Portland, Oregon, and open a legitimate business. He actually succeeded at it and for a while they were happier. Yet Frank drank heavily, which sent him into terrible rages. He'd whip his sons severely. The boys soon learned that no matter what they said or did, their father simply wanted to brutalize them, all the while insisting that they love him. One time, Gary was abandoned on a park bench while his father went to scam someone and he ended up in an orphanage for several days.

As he grew older, Gary reacted. He began to despise people in authority, and they in turn, treated him in a way that reminded him of his father. Both parents turned a blind eye to his problems, pretending they would just go away somehow. Neither respected the law, and they would rather get their children off than let them learn the consequences of their actions. The point at which psychological intervention might have made a difference for Gary, Frank refused to pay for it. On top of all of this, Bessie had a deep-rooted superstition about Gary that went back to her own childhood. She believed that as a girl playing with a Ouija board, she had conjured up a demonic ghost that had attached itself to her family. When one of her sisters was killed and another paralyzed in an accident, she felt certain it was the ghost. Then she married Frank and found out that his mother, Fay, was a medium who could get spirits to materialize. One night while at Fay's house with three of her sons, including Gary, she learned that there was to be a "special" séance to contact a spirit who had died under the shameful suspicion of murder. Bessie stayed away.

After the ceremony, she found Fay in a state of exhaustion with an expression on her face of great fear and helplessness. She helped the older woman to bed, but later that night Bessie woke up to the feel of being touched, and when she turned over, she was looking into the face of a leering inhuman creature. She jumped out of bed and saw Fay, an invalid, staggering toward her, insisting that she get out now. "It knows who you are!" Fay shouted. Bessie ran to Gary's room and saw the same figure leaning over her son, staring into his eyes. She grabbed the kids and ran. Fay died shortly thereafter and Gary began to have terrible, shuddering nightmares that he was being beheaded. He was certain something was trying to get him and the nightmares haunted him the rest of his life.

Bessie saw the entity again in their house, and that's when Gary began to get into trouble. He continued having dreams, swearing that something was in the room with him. Bessie concluded that the thing had taken over her son's soul. His life thereafter was filled with angry, malevolent energy that seemed bent on self-destruction. Whether influenced by a demon or by familial abuse, Gary developed a death wish that guided his actions. He seemed destined to die in some violent manner, though he'd often heard his mother's horror stories of an execution that she claimed to have witnessed as a girl. She'd been enraged that her father had taken her, a mere child, to witness a hanging. She told this story over and over. All of the boys believed that she'd really witnessed this incident and it had left a deep impression on them.

Yet when Mikal researched it in Utah records, he realized that it was impossible for her to have witnessed such an event. She had made it up, possibly deriving this metaphor from her helplessness and anger. Yet it was a fatal vision that may have marked her second son with a sense of inevitability. Mikal concludes that the lies she told revealed terrible psychological truths that became an unspoken emotional legacy for her sons. They wanted to erase themselves from existence, and in fact, one was murdered, one was executed, one dropped into a psychological coma ...and one (Mikal) became a writer.

The Trial

Two public defenders, Craig Snyder and Mike Esplin, took on Gilmore's case, but it looked pretty hopeless. There was an eyewitness who placed him near the Bushnell murder with the cash box and gun in his hand, and to top it all, he'd shot himself with the same gun. Then there was his cache of stolen guns, not to mention his apparent confession to a cop and later to his cousin. He'd told Brenda to tell his mother "it was true." As vague as that was, the jury could construe it as an admission of guilt. Their best hope was to find some legal technicality and take it to an appeals court.

While Noall Wootton was asking for the death penalty on the grounds that Gilmore was a danger to society should he ever escape and a threat to other inmates if sent to prison, no one had been executed in Utah for sixteen years. Wootton wasn't a death penalty advocate, but he did believe there was no possibility for Gilmore's rehabilitation. And even if he managed to get this sentence, he believed there was small likelihood of its being carried out.

Gilmore's trial lasted only two days, starting on October 5, 1976. The transcripts lay out the main events: An FBI ballistics expert matched two spent cartridges and the bullet from Bushnell to the gun left in the bush, a patrolman had traced Gilmore's trail of blood to that same bush, and the witness named Gilmore as the person he saw at the motel. The defense had no defense. When the two lawyers quickly rested without calling witnesses, Gilmore protested. The following day he asked the judge if he could take the stand to present his own defense. He figured that, based on what they had heard from the prosecution, it would take the jury less than half an hour to convict him and he wanted the chance to tell his story. He thought he had a good case for insanity. After all, he'd felt completely dissociated during the commission of the crime, like it was inevitable and he couldn't have done anything differently. He didn't have control.

His lawyers stood up and indicated that they had consulted four separate psychiatrists, all of whom had said that Gilmore had known what he was doing and that it was wrong. While he did have an antisocial personality disorder, which may have been aggravated by drinking and Fiorinal, he still did not meet the legal criteria for insanity.

Faced with that, Gilmore withdrew his request. He seemed suddenly to resign himself to the hopelessness of his situation. He'd already experienced some remorse for what he'd done but thought he'd probably end up doing it again. Never had he felt so much pain as that week without Nicole, according to what he said in his letters to her, and he knew he'd have kept up the spree, mindlessly hurting others.

In closing, Wootton took pains to point out that Ben Bushnell had been shot by a gun held directly against his head. It had been no random shot but quite deliberate.

Esplin countered with the fact that Gilmore himself had been wounded by the gun going off accidentally. It could have been the case that it had discharged accidentally in the incident that had resulted in Bushnell's death, even if held against him. Maybe Bushnell had moved suddenly. Since there are no eyewitnesses, who was to say differently? He urged the jury to find Gilmore guilty of a lesser crime of second-degree murder committed during a robbery, or even to acquit him altogether.

On October 7, 1976, after an hour and twenty minutes, the jury returned a verdict of Guilty of Murder in the First Degree. Then after lunch, the sentencing phase — called the Mitigation Hearing-- began. Again, the defense lawyers were at a disadvantage, since it was Gary's own family who had turned him in. Clearly they were afraid of him. Brenda felt that Gilmore had betrayed her trust and that he ought to pay for what he'd done. Getting good witnesses looked pretty hopeless. Yet no one could have predicted at that moment that Gilmore's own worst enemy in this regard would be himself.

At the end of the hearing, Gilmore was asked if he had anything to say, with the expectation that he would show some remorse, but all he said was, "I am finally glad to see that the jury is looking at me."

The sentence was death, arrived at unanimously, and to be carried out on November 15, just over a month hence. Gilmore was asked to choose between being hanged or shot by a firing squad. He chose the latter, believing that a hanging could easily be botched. While his attorneys prepared the expected course of action, Gilmore took the unexpected one.

Backlash

Although his attorneys had every intention of running an appeal, they told Mailer, Gilmore made up his mind to accept his due. He fired Esplin and Snyder and hired Dennis Boaz, a lawyer from California who had written to him on a whim in support of his desire to go through with the execution. Boaz also revealed his interactions with Gilmore to Mailer, who talked with various other people who'd spoken to Boaz. Gilmore traded an exclusive interview for the man's services, but as Mailer saw it, Boaz got hungry for the writer's life and started talking too much to the media. Gary decided to fire him.

Yet the very idea that a man was going to be executed stirred the residents of Utah into attention. This hadn't happened in sixteen years. To top it off, in 1972 the U. S. Supreme Court had ruled in the case of Furman v. Georgia that the death penalty as currently applied was cruel and unusual. Therefore, it was unconstitutional. All states were ordered to commute death sentences to life imprisonment. There was no more death row. Then four years later, after the states had revised their laws, the Supreme Court made a series of rulings that allowed capital punishment to be reinstated for certain types of murders. Thus, as of July 2, 1976, just three weeks before Gilmore committed his murders, such an act became a capital offense in Utah, and not without considerable controversy. While the hiatus had only lasted four years, it had been ten full years since the U. S. had executed anyone.

Then when Gilmore said that he did not wish to appeal, the Attorney General, Earl Dorius, wondered if the court might be caught in a net of its own making. Gilmore was supposed to be executed within sixty days of sentencing. There were no provisions for what might happen if they didn't get the deed done within the scheduled time frame. They hadn't executed a man in so long he couldn't be certain that they'd be ready in time. Dorius wondered if it was possible that, on a technicality, Gilmore might just go free. In fact, as he indicated to Mailer, he wasn't altogether certain how to put together a firing squad.

Just a few days before his scheduled execution, Gilmore argued his case before the Justices of the Utah Supreme Court, insisting that he did not wish to spend his life in prison, particularly not on death row. He thought the sentence was fair and proper and he wanted to accept it like a man. "It's been sanctioned by the courts," he said, "and I accept that."

To his mind, it was his karma to die. He'd had dreams of it all his life and had come to believe that he owed a debt from a past life. The manner in which he was to die would be a learning experience for others. That was all right with him. By a vote of 4 to 1, the Justices granted his wish. He requested that his last meal be a six-pack of beer.

But there were groups who could not abide such a decision, either on Gilmore's part or on the part of the law. The protests began at once, and his former lawyers felt duty-bound to continue to file an appeal. When Gilmore's mother heard about it, she told her youngest son. Mikal's comment, according to Mailer, was not to worry. "They haven't executed anyone in this country for ten years," he said, "and they're not going to start with Gary."

November 15th came and went. Associations against the death penalty, including the American Civil Liberties Union and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, intended to stop this execution. They did not want such a precedent on the record of the court giving in to a defendant and dispensing with the appeals process. On behalf of the prison population, as well as future prisoners, they felt they could not allow this procedure to continue in the direction in which it was going. A Stay of execution was granted, despite Gilmore's protests. He was ready to die. He wanted this over with.

Then he and Nicole formed a plan, which was documented in their letters to each other. She also admitted to it later in filmed interviews. Gilmore instructed her to go around to various doctors to collect as many barbiturates as she could get. She managed 50 pills. Smuggling half in a balloon inside her vagina, she handed them over to Gary. Then at midnight, she swallowed her dose. Gary was supposed to do likewise, but he waited till closer to morning, which gave the appearance that he wanted her to die while he was found and saved.

In fact they both survived, but now Nicole was effectively cut off from her lover. There were to be no more communications between them. Nicole was signed in to a psychiatric facility for observation.

In the meantime, the rights to Gilmore's story were up for sale. He authorized Uncle Vern to negotiate, and he ended up selling to Lawrence Schiller and ABC for $50,000, which Gilmore distributed randomly among relatives and former associates from prison.

He fully expected to die in December. Authorizing another lawyer, Ron Stanger, to speak on his behalf, he went before the Utah Board of Pardons to plead his case once more and ask all the religious and civil rights groups to butt out. "It's my life and my death," he insisted on film. He hadn't realized that no one had taken the sentence seriously. He didn't know it was all a joke. He expected that if they were going to hand it down, they were going to carry it out. As he spoke, his courage and anger were both evident. He wanted this over with.

His execution was set for December 6, two days after his thirty-sixth birthday.

Then on December 3, Gilmore's mother stepped in. She was represented by the same lawyer whose rhetoric had convinced the Supreme Court to stop capital punishment several years earlier until the laws were changed. She requested a Stay on her son's behalf. He'd been on a hunger strike ever since he'd been separated from Nicole, she claimed through the lawyer, so he didn't know what he was doing. She should be able to step in.

Gilmore composed an open letter to her, published by the press, to ask that she allow him to get on with it. Ten days later, the Stay was overturned and Gilmore ended his 25-day hunger strike. Upon learning that he would still have to wait another month for his execution, he tried once again to kill himself, but was found in time.

Then Mikal decided that he needed to try to stop the process. He went to Utah to talk with his brother, describing the meeting in detail in his book, and was ultimately convinced that Gary knew what he was doing and wanted to do it. On film, Mikal said that Gary had quoted Nietzsche to him, that "a time comes when a man should rise to meet the occasion." That's what he was trying to do. During their last meeting, Gary kissed Mikal on the mouth and said, "See you in the darkness." Mikal left without taking any further action.

Finally it was scheduled for January 17, 1977. Overnight, the courts had continued to wrestle with the legal questions before them. A federal court judge in Salt Lake City ordered a Stay, but the Tenth Circuit Court in Denver set it aside. The ACLU continued to protest this right up to the moment that Gilmore began his walk as a dead man. Even as late as 7:30 a.m., Gilmore's fate hung in the balance.

It was the U. S. Supreme Court that finally decided the issue. The execution was allowed to go on as scheduled.

The End and the Beginning

The night before he was to die, Gilmore had been given plenty of drugs. His relatives visited and he was in good spirits. Uncle Vern admitted on A&E that he'd brought him some whiskey, which Gilmore drank down. Then Johnny Cash, his favorite singer, called and sang him a song. Gilmore tried to sing it with him. Then he made a tape for Nicole on which he asked her to kill herself for him. Finally, the circus was over. All of those who believed the con was bluffing, that he'd change his mind at the last minute, were in shock. Gilmore had asked to be allowed to die and he was going to die.

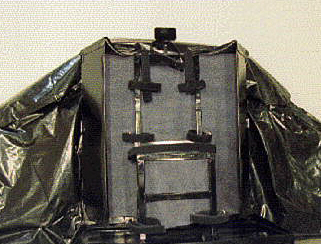

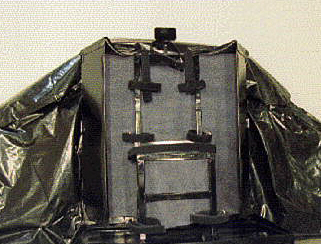

At 8:00 a.m. on January 17, 1977, the volunteer firing squad got into place. Four of the five weapons were loaded and one would fire a blank. That way, each man would have some idea that perhaps he was not the one who had ended another man's life. They placed the barrels of their rifles through small square holes in a wall as Gilmore was strapped into a chair. He gave his watch to Vern to give to Nicole; he'd broken it at his estimated time of execution. A paper target was placed over his heart and a black corduroy hood over his head. He was strapped into the chair. The least movement could make the bullets miss their mark.

Mailer gives a full account of the final minutes, which were also described on film by some of those who attended.

Asked for last words, Gilmore said, "Let's do it." Then to the priest delivering last rights, he said in Latin, "There will always be a father." The countdown began. Gilmore appeared calm. There were three distinct shots. His head went forward into the strap, his right hand delicately lifted, then dropped. The spectators he'd requested to witness the event watched as blood flowed from his heart down his shirt and onto the floor. The doctor went forward to listen, and said that he was still alive. In twenty more seconds, it was over.

Three lives had been tragically wasted.

Bessie got the news that there had been a Stay, but then she saw on the television that her second son, Gary Mark Gilmore, had been executed. Some of his organs were donated before he was cremated, and his ashes were spread in three designated areas of Utah, including Spanish Fork.

His immortal words, "Let's do it," opened the door for other convicted criminals to be put to death. Since 1977, there have been 711 executions in the United States.

[Katherine Ramsland has written a dozen books and numerous articles, as well as publishing folklore and short stories. After publishing two books in psychology, Engaging the Immediate and The Art of Learning, she wrote Prism of the Night: A Biography of Anne Rice. At that time, she had a cover story in Psychology Today on our culture's fascination with vampires. Then she wrote guide books to Anne Rice's fictional worlds: The Vampire Companion: The Official Guide to Anne Rice's Vampire Chronicles, The Witches' Companion: The Official Guide to Anne Rice's Lives of the Mayfair Witches, The Roquelaure Reader: A Companion to Anne Rice's Erotica, and The Anne Rice Reader. Her next book was Dean Koontz: A Writer's Biography, and then she ventured into journalism with Piercing the Darkness: Undercover with Vampires in America Today. She has also written for The New York Times Book Review, The Writer, Million: The Magazine of Popular Fiction, The Newark Star Ledger, Magical Blend, Publishers Weekly, and The Trenton Times. Her background in forensic studies positioned her to assist former FBI profiler John Douglas on his book, The Cases that Haunt Us. Ramsland holds master's degrees, respectively, in clinical and forensic psychology and a Ph.D. in philosophy. She has been a professor at Rutgers University, a therapist, and a psycho-educator specializing in the psyche's dark side.]

Executions Out of the Ordinary

During the 1950s and 1960s 10 states, including Michigan and New York, abolished the death penalty and the rate of executions nationwide began to decline.

By 1968 executions had stopped and in 1972 the Supreme Court ruled, in the case of Furman v Georgia, "that the imposition of the death penalty constituted cruel and unusual punishment".

But 35 states responded by drafting new death penalty statutes and in 1976 the Supreme Court reversed its decision, ruling that the punishment of death did not violate the constitution provided that "guided discretion" was exercised in imposing it.

In October 1976 Gary Gilmore was convicted of a double murder in Utah and sentenced to death. Gilmore, who had spent much of his life in prison, could not bear the prospect of spending years behind bars and decided not to appeal the sentence. The American Civil Liberties Union appealed on his behalf - and to his annoyance - but on 17 January 1977 Gilmore was executed by firing squad, the first execution in the US for a decade. Norman Mailer later wrote a book about Gilmore, The Executioner's Song, which was made into a TV movie starring Tommy Lee Jones.

Washington Post (January 18, 1977) by William Greider.

PROVO, Utah - Early this morning at the mountain prison, attended by scribes and camera crews, the state of Utah delivered Gary Mark Gilmore back to his maker.

Gilmore was judged defective as a human being in October. Last summer he

murdered 2 Utah citizens, a service station attendant named Max Jensen and a motel clerk named Bennie Bushnell. While in prison awaiting execution, Gilmore twice tried to kill himself and insisted that the legal authorities proceed to do it for him without further delay.

This morning the government of Utah complied, despite a last-minute legal flurry from civil liberties lawyers. It was done as tastefully as possible under the circumstances. Gilmore was taken to a cinder block shed, strapped in a chair and shot.

As easy as pouring blood into water. Gilmore, alive for 36 unsuccessful years, attained celebrity by being the subject of the 1st American execution in nearly a decade. His official last words to the warden, witnesses and 5 anonymous gunmen with their .30-cal. rifles was: "Let's do it."...

It was an unpleasant spectacle -- not the killing itself, which was done in privacy, but the swarming attention and brittle humor of the news media, which, after all, made Gilmore into a mythical creature larger than his real self, perhaps made him even enviable to others with freakish wishes for self-destruction. For those who need to know these things, Gilmore bled profusely when shot. The prison people pinned a paper target to his clothing, over his heart, and 4 riflemen hit it (1 of the 5 had a blank in his gun though nobody is supposed to know which one).

The scene was then cleaned up a bit before the press was taken in to look it over. Some sort of gravel was spread around the platform to cover the blood stains under the black leather arm chair. The chair had been wiped clean but it had 4 bullet holes in its back, stained with blood, and there was a drying trickle of blood on the plywood board behind where Gilmore had sat. The 4 slugs are presumably still buried in the backstop of sandbags and a flowered mattress -- valuable souvenirs if anyone takes the trouble to retrieve them.

Gilmore, it was reported by an eyewitness, did nothing untoward at the moment of his death. He did not quiver with fear. He did not shrink from the black corduroy hood placed over his head and shoulders, did not struggle or cry out at the last moment. His head turned slightly when he was shot. His body shrugged a trifle. That's all.

(source: Washington Post)

"Norman Mailer, Gary Gilmore, and the Untold Stories of the Law," by Simon Petch.

Early in the morning of Wednesday July 21 1976 Gary Gilmore was arrested in Provo, Utah, on suspicion of the murder of a motel owner in Provo on the previous Tuesday evening, and of a gas station attendant, in nearby Orem, on the Monday night. At the time of the killings Gilmore was on parole from a twelve-year sentence for armed robbery, and was being harboured by relatives. He was effectively turned in by his cousin Brenda Nicol, who told him, by way of explanation: "You commit a murder Monday, and commit a murder Tuesday. I wasn't waiting for Wednesday to come around". In October of the same year Gilmore was tried, convicted, and sentenced to death. Offered a choice as to the mode of execution, he opted to be shot. Both victims had been Mormon, and, in the opinion of his brother Mikal, Gary exercised his choice in knowing fulfillment of the Mormon doctrine of Blood Atonement. 1

The sentence was carried out six months after the murders: on Monday January 17 1977, a few minutes after 8am local time, Gary Gilmore was executed by firing squad in a disused cannery in Utah State prison. It was the first judicial homicide in the United States for ten years, and it had not, from a legal point of view, been easy to organise.

The date first set for the execution had been November 15 1976, and on November 1 Gilmore announced his intention not to appeal against his sentence. His refusal to appeal galvanised the American Civil Liberties Union and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People to make strenuous attempts to stop this execution, on behalf of the many prisoners on death row throughout the United States for whom it could be a fatal precedent. Several judicial Stays delayed the execution for two months, and the appeals continued until the end. Within ten minutes of the time scheduled for the execution, the ACLU--in extremis after a night of legal turmoil in which a Stay ordered in Salt Lake City by a Federal Court judge had been set aside by the Tenth Circuit Court in Denver--unsuccessfully petitioned the Supreme Court in Washington for a final Stay of execution.

More than a dozen years before the Gilmore case, Truman Capote compared "the system of appeals that pervades America jurisprudence ...to a legalistic wheel of fortune, a game of chance ...that the participants play interminably, first in the state courts, then through the Federal Courts until the ultimate tribunal is reached--the United States Supreme Court. But even defeat there does not signify if petitioner's counsel can discover or invent new grounds for appeal; usually they can, and so once more the wheel turns ...But at intervals the wheel does pause to declare a winner--or, though with increasing rarity, a loser". 2

Gilmore's unwavering refusal to play the game put him in the paradoxical position of a defendant who apparently agreed with the prosecution. It consequently put a spoke in the wheels of justice by jamming the usual process of argument and counter-argument through which the adversarial discourse of the law sustains itself. This denial of habitual procedure led to near panic in the legal institution, but the law came to its own rescue: the courts of Utah and the Federal Tenth Circuit Court between them restored some semblance of an adversarial context through which the untidy legal plot could be knocked into the shape of a judicial narrative. The appeals process exhausted itself at about the same time as the triggers were due to be squeezed, and, as if in gracious acknowledgment to all concerned, the United States Supreme Court provided the closure that is the necessary constraint of all legal story-telling. Gilmore had fought the law and won, but he could only win by losing, and so the law itself could reasonably claim victory too.

Gilmore's paradoxical position of having to lose the game in order to win it, and his disturbance of the processes by which legal stories are produced, suggested imaginative spaces in which alternative stories about him could be told. In The Executioner's Song (which follows Gilmore from his release on parole in April 1976 to his execution nine months later), Norman Mailer gives shape to some alternative stories by exploiting the tension between legal and other ways of talking about Gary Mark Gilmore.

The Executioner's Song, which Mailer calls a 'true life story', is on the cusp of legal and novelistic discourses. Its fictive methods play law and literature against each other. As it draws out the stories which lie just beneath the surface of legal narrative--stories which the law suppresses because it apparently has no interest in them--the novel amplifies that which the law would suppress or exclude. And in these processes the novel challenges the authority of legal story-telling.

On July 22 1976, the day after his arrest for murder, Gilmore made a private call (from the police station in Orem, to which he had been transferred) to Brenda Nicol. The call was important to Gilmore's trial, and also to The Executioner's Song, in which Mailer's first account of this call is economical and direct: Brenda said, 'Gary, you're going to go down hard this time. You're going to ride this one clear to the bottom.' He said, 'Man, how do you know I'm not innocent?' 'Gary, what's the matter with your head?' 'I don't know,' Gary said, 'I must have been insane.' Brenda asked, 'What about your mother? What do you want me to tell her?'

He was quiet for a while. Then he said, 'Tell her it's true.' Brenda said, 'Okay. Anything else?' 'Just tell her I love her.'

The evident clarity of this conversation was muddied in the courtroom, where Gilmore's words came back to haunt both him and Brenda through her testimony at his trial. Her very presence at the Preliminary Hearing (the first stage of the trial) created misunderstanding, for Gilmore thought she was there to see him, although she had in fact been called as a witness by the prosecution. She "told of the phone call Gary made from the Orem Police Station", Mailer wrote. "'I asked him what he would like me to tell his mother,' Brenda had said on the stand. 'He said, I guess you can tell her it's true.' Mike Esplin [for the defence] tried to get Brenda to agree Gary meant it was true he had been charged with murder. Brenda repeated her testimony and took no sides. Gary found that hard to forgive". Esplin intensifies the situation for Brenda by trying to pin her down to a particular interpretation of Gilmore's words, but she refuses to agree, and the refusal creates tension between her and Gilmore.

The increasing complication of the relationship between Gilmore and Brenda is rendered through the thickening of the narrative style, and is beautifully suggested by the final sentence. By expressing Brenda's unease about Gilmore's response to her testimony, "Gary found that hard to forgive" tells us much as about Brenda's feelings as it does about Gilmore's; it subtly shifts the legal discourse of the courtroom exchange into an exploration of the relationship between the cousins. The feelings of both are indirectly rendered through Brenda's apprehension about Gilmore's response, and Mailer's economical sentence moves freely between them. As a narrative device through which he can explore alternative dimensions of meaning latent in but suppressed by legal discourse, such free indirect discourse is Mailer's most powerful counter-legal strategy. It enables him to take the reader away from the determinate jurisdiction of the court, and to bring other systems of value into play. 3

The gradual reworkings of the telephone conversation as testimony take increasing account of Brenda's feelings, and the legal interpretation of Gilmore's words becomes secondary to the more emotionally-charged issues of loyalty and responsibility. Mailer progressively nudges Brenda's testimony into the meanings it has beyond the law, and as the conversation is transferred from the police station to the court its imprecision bristles with the complexity of Gilmore's relationship with Brenda.

Brenda Nicol's conscience, and her sense of social responsibility, are significantly non-legal points of reference throughout The Executioner's Song, and she was also one of the main sources of Mailer's information about Gilmore's life between his release from prison in April 1976 and his arrest three months later. Mailer must have learned about the phone call and the testimony from her. As far as possible in The Executioner's Song Mailer presents Gilmore (whom he never met) in his own words as they were recorded or remembered, and reproduces them directly, as in this conversation. This method permits Mailer's Gilmore to speak from a number of positions to a number of audiences, whose responses or reactions are then used as a commentary or gloss on what Gilmore says. Such responses are usually given in the free indirect style described above, a narrative technique which indicates Mailer's access to the minds of his sources and which is used to establish relationship between them and Gilmore. As Gilmore's words are registered through the particular and individual perspectives of those who heard him, this technique creates an audience-effect. It enables Mailer to transcend the legal discourse on which so much of the novel is based, and the meanings that were closed off in court are opened and explored, in the novel, on levels beyond the law. This is what happens both to Gilmore's words to Brenda, and to Brenda's testimony, and these exchanges between them, direct and indirect, richly illustrate the sensitivity of the novel's discourse to the extra-legal levels on which the language of the law operates...

Unlike Capote's In Cold Blood, Mailer could claim no personal relationship with his subject, and he makes no attempt to mount a case for him. But Mailer swerves most radically from his precursor in that he claims no access to the mind of his subject beyond what he is recorded as having written or said: The Executioner's Song uses no free indirect discourse for Gilmore himself, whose meanings are interpreted or rendered through what I have called the audience-effects of his words. This method establishes Gary Gilmore less as a continuous personality than as an enigma, whose multiple meanings are simultaneously increased and delimited by the urgency and intensity of others' responses to him.

Like Capote, Mailer criticizes the ways and means by which a trial narrative was produced. But the methods of Mailer's 'true life story' are more radical than those of Capote's 'non-fiction novel'. For by opening the ambiguous meanings of testimony and evidence into fictional possibilities the novel challenges the hermeneutics of the law, and through the epistemological insecurity afforded by its free indirect discourse it suggests levels of meaning unacknowledged by legal institutions. Brook Thomas has recently argued that literature, like equity, exists in supplemental relation to the law, and has claimed that literature should provoke us into new ways of understanding by pointing to what he calls the untold story of the law. Such provocation, claims Thomas, may "stimulate an audience to generate new ways of constructing evidence, evidence that does not easily fit into accepted public opinion, evidence that is not deemed admissible in existing courts of law. If accepted, such evidence can alter a society's sense of justice." 4 In The Executioner's Song the untold stories that gather around Gilmore challenge both the interpretive practices of the law and the justice dispensed by the institutions of the state, and liberate him, not from his guilt, but from the 'legal processing' to which he was subject.

Gilmore, who had been executed, autopsied, cremated, and dispersed several months before Mailer signed his contract, is continuously re-formed, in The Executioner's Song, as a series of shifting reference-points in the complex socio-cultural network of the United States of America in its Bicentennial year of 1976, in which the Vietnam war is a bad dream from which the country has barely wakened, and in which Mormonism is a long-surviving embodiment of the Old Testament Puritan fundamentalism on which the country was founded. In this, his Great American Novel of the seventies, Mailer's avowedly fictive methods interrogate the unacknowledged fictions of the law, and crack the codes of his country's conscience. By releasing the stories the law did not know, or could not or would not tell, the rhetorical strategies of The Executioner's Song endorse Shelley's famously radical claim that poets--for which we can today read 'writers'--are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.

[Simon Petch teaches Literature at Sydney University and is a past president of the Literature and Law Association of Australia.]

Notes and References

1. Norman Mailer, The Executioner's Song, 1979

2. Truman Capote, In Cold Blood: A True Account of Multiple Murder and Its Consequences, 1965

3. The term 'free indirect discourse' is used here as it is defined by Cohan and Shires, that is as a narrative mode which 'conflates monologue and psycho-narration, with the narrator seeming to mimic the voice of the character who functions as focalizer and focalized. For this reason the narration is "free," not limited to what the character thinks exactly, and "indirect," using language which the character himself could conceivably use but narrating rather than quoting it.' Steven Cohan and Linda M. Shires, Telling Stories: A Theoretical Analysis of Narrative Fiction (London: Routledge, 1988), 102.

4. Brook Thomas, 'Reflections on the Law and Literature Revival', Critical Inquiry 17:3 (Spring, 1991), 537-38.

The Execution of Gary Gilmore

At eight minutes after 8:00 a.m on January 17, 1977, Gary Mark Gilmore was executed by a firing squad in Draper, Utah. The execution ended the life of a man who had killed at least two people and who had spent 18 of his 36 years behind bars for various offenses. Two aspects of the case kept it on the front pages for months. First, the death penalty had been reinstated in the United States in 1976 (not without controversy) after a 10-year hiatus and Gilmore was to become the first prisoner to be executed. Second, he fought the justice system to ensure he would be executed quickly.

In Cold Blood

Over the course of two nights in mid-July 1976, Gary Gilmore murdered a motel owner (Bennie Bushnell) in Provo, Utah and a gas station attendant (Max Jensen) in nearby Orem in an apparent attempt to get the attention of his estranged girlfriend Nichole Baker. Both men were forced to lie face down on the floor before he shot them in each in the head at point-blank range.

Capture

In the early morning hours of July 21, 1976 Gary Gilmore was arrested in Provo, Utah for the murders of the two men. At the time of his arrest Gilmore was on probation from a 12-year sentence for armed robbery and had been staying with relatives. He was turned in by his cousin Brenda Nicol, who later told him "You commit a murder Monday, and commit a murder Tuesday. I wasn't waiting for Wednesday to come around."

Speedy Trial

One of the most remarkable aspects of the case was the speed at which he went through the justice system. He was that he was arrested in July, then tried, convicted, and sentenced to death by October and the sentence was carried out in January. The pace was no accident.

Multiple Suicide Attempts

Not satisfied with the amount of time the state was taking to execute him, Gilmore tried to speed things up with repeated suicide attempts (by drug overdose) and became front page news for this, the attempts by others to stop the execution, and his own refusal to make any appeals. He had said "Death is the only inescapable, unavoidable, sure thing. We are sentenced to die the day that we are born." His girlfriend Nicole also tried to take her own life at the same time as him. She failed too and was placed in a mental hospital and was not allowed to see Gary again. The only contact she had with him until his execution was via letters.

Multiple Appeals

His original execution date was November 15, but the ACLU (American Civil Liberties Union) and the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) - both death penalty opponents - filed motions in the courts and multiple Stays were ordered. But the final appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court on the morning of January 17th, 1977 was denied and Gilmore's wish to be executed was granted. It had been only nine months since he had been paroled.

Firing Squad

When asked if he had any last words by the warden, he simply replied "Let's do this." As is the custom with a firing squad, four of the five rifles were loaded with real bullets and the fifth had a blank (None of the members knows which gun is which. This leaves a shadow of doubt in each member's mind about whether or not they really killed him.) He was shot at 8:08 a.m. and pronounced dead a minute later. His body was cremated and his ashes spread over three areas in Utah by a family member in accordance with his wishes.

Executioner's Song

The Executioner's Song (http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/asin/0375700811/allinterviewscom), a book written by Norman Mailer in 1979, is a must read if you are interested in reading about the Gilmore case. The book, which won a 1980 Pulitzer Prize, was later turned into a made-for-TV movie starring Tommy Lee Jones, Eli Wallach and Rosanna Arquette. Jones won an Emmy for his portrayal of Gilmore.

"The Story of Gary Gilmore: Executioner's Song by Norman Mailer and Shot in the Heart by Mikal Gilmore," by Scott Vollum, Doctoral Student, College of Criminal Justice, Sam Houston State University.

I submit these two books together because they are, in many ways, good companions to one another. Together, these two books provide you with a thorough history and analysis of a single criminal--Gary Gilmore. After reading both of these books you feel like you actually know and understand Gary Gilmore and what drove and motivated him to his criminal acts.

EXECUTIONERS SONG

In Executioner's Song, Norman Mailer's Pulitzer Prize winning novel, we are presented with the adult criminal life of Gary Gilmore and the resulting execution that would be the first in America since the Furman v. Georgia decision. The book starts with Gilmore getting out of prison, follows his failed attempts at a "legitimate" life, the events leading up to a killing spree, and the resulting path back through the justice system. This time, however, he would not be released back into society. He was sentenced to death and in response demanded that the sentence be carried out. He refused to cooperate in any attempt to appeal his death penalty sentence and even went so far as to challenge the system to put actions to their words. This is significant because no one had been executed since the Furman case. Gary Gilmore would force the hand of a system that was reluctant to begin executing people again. Arguably, he opened up the flood gates for the implementation of the death penalty in the decades that were to follow.

Executioner's Song paints a very thorough portrait of a man driven to murder and to eventually demanding the end of his own life. In regard to the Sutherland's three elements of Criminology: The making of law, breaking of law, and reaction to the breaking of law, they are all represented in this book.

Making of Law:

The representation of the making of law in Executioner's Song is not explicit but the execution of Gary Gilmore began a new era for the use of death as a punishment in American society effectively making it part of law once again. Also, the question of whether the state can force an individual to adhere to the appeals processes so important in death penalty cases was asked. Ultimately, there was a situation in which the offender was asking the state to take his life. This raises a lot of potential legal issues surrounding the death penalty. The door was closed on these issues when the execution of Gary Gilmore was carried out. While these are not explicit examples of the portrayal of the making of law, they were important events that molded the way the death sentence is perceived and implemented under the law.

Breaking of Law:

The representation of the breaking of law is more clear and pervasive in Executioner's Song. We are presented with a good example of a life-course-persistent criminal in Gary Gilmore. We are also presented with some good examples of Agnew's General Strain Theory at work. Gary Gilmore is a man that wants things in life but does not see the legitimate means to obtain them as existing for him. He feels that the world is against him and reacts to this with anger and violence. The many forms of strain that persisted throughout Gary Gilmore's life resulted in frustration and anger that ultimately led to a murderous rampage.

Reaction to the Breaking of Law:

The reaction to the breaking of law is clear in this book. This books depiction of Gilmore's adjudication and time spent in prison and ultimately his execution are great examples of the system at work.

SHOT IN THE HEART

Shot in the Heart, too, presents us with the life of Gary Gilmore. However, this book is written by his youngest brother and presents us with a portrayal of Gilmore's childhood and life growing up in a family with an abusive father. This book gives us the background from which Gary Gilmore came and provides a deeper understanding of the man presented to us so well in Mailer's Executioner's Song. What we begin to see, as this book chronicles Gilmore's young life, is the genesis of a murderer. The crime correlates of social class and family are clearly analyzed in this very poignant account of a future murderer's upbringing.

Famous Cases

Killed by a firing squad just after 8 a.m. on Monday, Jan. 17, 1977, Gilmore became the first convict to be executed in the United States after a near-decade pause following a Supreme Court ruling. Gilmore, who had asked to be executed, had been convicted of murdering Bennie Bushnell and Max David Jensen, both shot during robberies.

Asked if he had any last words, Gilmore said, "Let's do it." Gilmore, who had vowed not to flinch before the firing squad, sat placidly, a hood covering his head, as five anonymous gunmen armed with .30-caliber rifles took aim and fired. Four of the rifles were loaded with live ammunition; one held a blank.

Prior to his execution, Gilmore drew attention with two suicide attempts by drug overdose and his pleas for death.

Gilmore's uncle, one of the only people to have close contact with the convict before his death said of the execution, "I would like to say at this time, Gary, my nephew, died like he wanted to die, in dignity. He got his wish to die. He died in dignity. That's all I have to say."

At the time there were 358 other Americans - including four women - on death row throughout the country. Gilmore's death publicly marked the resumption of executions in the United States.

![]()