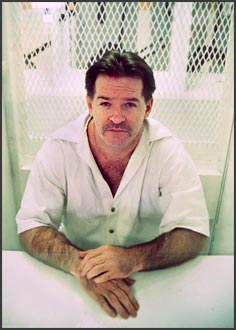

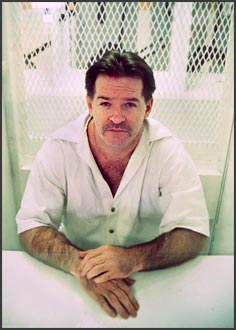

(Bill West)

|

| The center of the storm: Convicted murderer and rapist Ricky McGinn at Terrell prison in Livingston, Texas. (Bill West) |

Special Report: DNA and other evidence freed 87 people from death row; now Ricky McGinn is roiling Campaign 2000. Why America's rethinking capital punishment.

He stood at the threshold of the execution chamber in Huntsville, Texas, 18 minutes from death by lethal injection, when official word finally came that the needle wouldn't be needed that day. The rumors of a 30-day reprieve were true. Ricky McGinn, a 43-year-old mechanic found guilty of raping and killing his 12-year-old stepdaughter, will get his chance to prove his innocence with advanced DNA testing that hadn't been available at the time of his 1994 conviction. The double cheeseburger, french fries and Dr Pepper he requested for dinner last Thursday night won't be his last meal after all.

Another galvanizing moment in the long-running debate over capital punishment: last week Gov. George W. Bush granted his first stay of execution in five years in office not because of deep doubts about McGinn's guilt; it was hard to find anyone outside McGinn's family willing to bet he was truly innocent. The doubts that concerned Bush were the ones spreading across the country about the fairness of a system with life-and-death stakes. "These death-penalty cases stir emotions," Bush told NEWSWEEK in an exclusive interview about the decision. Imagine the emotions that would have been stirred had McGinn been executed, then proved innocent after death by DNA. So, Bush figured, why take the gamble?

"Whether McGinn is guilty or innocent, this case has helped establish that all inmates eligible for DNA testing should get it," says Barry Scheck, the noted DNA legal expert and coauthor of "Actual Innocence." "It's just common sense and decency."

Even as Bush made the decent decision, the McGinn case illustrated why capital punishment in Texas is in the cross hairs this political season. For starters, McGinn's lawyer, like lawyers in too many capital cases, was no Clarence Darrow . Twice reprimanded by the state bar in unrelated cases (and handling five other capital appeals simultaneously), he didn't even begin focusing on the DNA tests that could save his client until this spring. Because Texas provides only $2,500 for investigators and expert witnesses in death-penalty appeals (enough for one day's work, if that), it took an unpaid investigator from out of state, Tina Church, to get the ball rolling.

After NEWSWEEK shone a light on the then obscure case ("A Life or Death Gamble, " May 29), Scheck and the A-team of the Texas defense bar joined the appeal with a well-crafted brief to the trial court. When the local judge surprised observers by recommending that the testing be done, it caught Bush's attention. The hard-line higher state court and board of pardons both said no to the DNA tests—with no public explanation. This time, though, the eyes of the nation were on Texas, and Bush stepped in.

But what about the hundreds of other capital cases that unfold far from the glare of a presidential campaign? As science sprints ahead of the law, assembly-line executions are making even supporters of the death penalty increasingly uneasy. McGinn's execution would have been the fifth in two weeks in Texas, the 132d on Bush's watch. Is that pace too fast? We now know that prosecutorial mistakes are not as rare as once assumed; competent counsel not as common. Since the Supreme Court allowed reinstatement of the death penalty in 1976, 87 death-row inmates have been freed from prison. With little money available to dig up new evidence and appeals courts usually unwilling to review claims of innocence (they are more likely to entertain possible procedural trial-court errors), it's impossible to know just how many other prisoners are living the ultimate nightmare.

So for the first time in a generation, the death penalty is in the dock—on the defensive at home and especially abroad for being too arbitrary and too prone to error. The recent news has prompted even many conservative hard-liners to rethink their position. "There seems to be growing awareness that the death penalty is just another government program that doesn't work very well," says Stephen Bright of the Southern Center for Human Rights.

When Gov. George Ryan of Illinois, a pro-death-penalty Republican , imposed a moratorium on capital punishment in January after 13 wrongly convicted men were released from Illinois's death row, it looked like a one-day event. Instead, the decision has resonated as one of the most important national stories of the year. The big question it raises, still unanswered: how can the 37 other states that allow the death penalty be so sure that their systems don't resemble the one in Illinois?

In that sense, the latest debate on the death penalty seems to be turning less on moral questions than on practical ones. While Roman Catholicism and other faiths have become increasingly outspoken in their op- position to capital punishment (even Pat Robertson is now against it), the new wave of doubts seems more hardheaded than softhearted; more about justice than faith.

The death penalty in America is far from dead. All it takes to know that is a glimpse of a grieving family, yearning for closure and worried about maximum sentences that aren't so long. According to the new NEWSWEEK Poll, 73 percent still support capital punishment in at least some cases, down only slightly in five years. Heinous crimes still provoke calls for the strongest penalties. It's understandable, for instance, how the families victimized by the recent shooting at a New York Wendy's that left five dead would want the death penalty. And the realists are right: the vast majority of those on death row are guilty as hell.

But is a "vast majority" good enough when the issue is life or death? After years when politicians bragged about streamlining the process to speed up executions, the momentum is now moving the opposite way. The homicide rate is down 30 percent nationally in five years, draining some of the intensity from the pro-death-penalty argument. And fairness is increasingly important to the public. Although only two states—Illinois and New York—currently give inmates the right to have their DNA tested, 95 percent of Americans want that right guaranteed, according to the NEWSWEEK Poll. Close to 90 percent even support the idea of federal guarantees of DNA testing (contained in the bipartisan Leahy-Smith Innocence Protection bill), though Bush and Gore, newly conscious of the issue, both prefer state remedies.

The explanation for the public mood may be that cases of injustice keep coming, and not just on recent episodes of the "The Practice" that (with Scheck as a script adviser) uncannily anticipated the McGinn case. In the last week alone Bush pardoned A. B. Butler after he served 17 years in prison for a sexual assault he didn't commit, and Virginia Gov. James Gilmore ordered new testing that will likely free Earl Washington, also after 17 years behind bars. All told, more than 70 inmates have been exonerated by DNA evidence since 1982, including eight on death row.

Death-penalty advocates often point out that no one has been proved innocent after execution. But the DNA evidence that could establish such innocence has frequently been lost by prosecutors with no incentive to keep it. In a recent Virginia case, a court actually prevented posthumous examination of DNA evidence. On the defense side, lawyers and investigators concentrate their scarce resources on cases where lives can be spared.

And while DNA answers some questions, it raises others: if so many inmates are exonerated in rape and rape-murder cases where DNA is obtainable, how about the vast majority of murders, where there is no DNA? Might not the rate of error be comparable?

Politics, for once, seems to be in the background, largely because views of the death penalty don't break down strictly along party lines. Ryan of Illinois is a Republican; Gray Davis, the hard-line governor of California, a Democrat . The Republican-controlled New Hampshire Legislature recently voted to abolish the death penalty; the Democratic governor vetoed the bill. Perhaps the best way to understand how the politics of the death penalty is shifting is to view it as a tale of two Rickys:

In January 1992, Arkansas Gov. Bill Clinton interrupted his presidential campaign to return home to preside over the execution of Ricky Ray Rector, a black man convicted of killing a police officer. Rector had lobotomized himself with a bullet to his head; he was so incapacitated that he asked that the pie served at his last meal be saved for "later." By not preventing the execution of a mentally impaired man, Clinton was sending a strong message to voters: the era of soft-on-crime Democrats was over. Even now, Al Gore doesn't dare step out front on death-penalty issues.

Ricky McGinn's case presented a different opportunity for Bush. While the decision to grant a stay was largely based on common sense and the merits of the case, it was convenient, too. In 1999, Talk magazine caught Bush making fun of Karla Faye Tucker, the first woman executed in Texas since the Civil War. Earlier this year, at a campaign debate sponsored by CNN, the cameras showed the governor chuckling over the case of Calvin Burdine, whose lawyer fell asleep at his trial. In going the extra mile for McGinn over the objections of the appeals court and parole board, Bush looked prudent and blunted some of the criticism of how he vetoed a bill establishing a public defenders' office in Texas and made it harder for death-row inmates to challenge the system.

That system has scheduled 19 more Texas executions between now and Election Day. Gary Graham, slated to die June 22, was convicted on the basis of one sketchy eyewitness account when he was 17. The absence of multiple witnesses would make him ineligible for execution in the Bible ("At the mouth of one witness he shall not be put to death"—Deuteronomy 17:6); and Graham's age at the time he was convicted of the crime in 1981 would make him too young to be executed in all but four other nations in the world.

Americans might not realize how upset the rest of the world has become over the death penalty. All of our major allies except Japan (with a half-dozen executions a year) have abolished the practice. Only China, Iran, Saudi Arabia and Congo execute more than the United States. A draft version of the European Union's Bill of Rights published last week bars EU countries from extraditing a suspected criminal to a country with a death penalty. (If approved, this could wreak havoc with international law enforcement). Admission to the EU is now contingent on ending capital punishment, which will force Turkey to abolish its once harsh death-penalty system.

The execution of juvenile offenders is a particular sore spot abroad. The United States has 73 men on death row for crimes committed when they were too young to drink or vote (mostly age 17); 16 have been executed, including eight in Texas. That's more than the rest of the world combined.

So far, opposition abroad has had little effect at home. What changed the climate in the United States was a series of cases in Illinois. The story traces back to the convictions of four black men, two of whom were condemned to die, for the 1978 murders of a white couple in the Chicago suburb of Ford Heights. In the early 1980s, Rob Warden and Margaret Roberts, the editors of a crusading legal publication called The Chicago Lawyer, turned up evidence that the four might be innocent. The state's case fell apart in 1996, after DNA evidence showed that none of the so-called Ford Heights Four could have raped the woman victim. It was only one case, but it had a searing effect in Illinois for this reason: three other men confessed to the crime and were convicted of it. The original four were unquestionably innocent—and two of them had nearly been executed.

By then other Illinois capital cases were falling apart. Some of the key legwork in unraveling bum convictions came from Northwestern University journalism students. Late in 1998 their school hosted a conference on wrongful convictions. The event produced a stunning photo op: 30 people who'd been freed from death rows across the country, all gathered on one Chicago stage.

But it was another Illinois case, early in 1999, that really began to tip public opinion. A new crop of Northwestern students helped prove the innocence of Anthony Porter, who at one point had been just two days shy of lethal injection for a pair of 1982 murders. Once again, the issue in Illinois wasn't the morality of death sentences, but the dangerously sloppy way in which they were handed out. Once again a confession from another man helped erase doubt that the man convicted of the crime, who has an IQ of 51, had committed it.

By last fall the list of men freed from death row in Illinois had grown to 11. That's when the Chicago Tribune published a lavishly researched series explaining why so many capital cases were suspect. The Tribune's digging found that almost half of the 285 death-penalty convictions in Illinois involved one of four shaky components: defense attorneys who were later suspended or disbarred, jailhouse snitches eager to shorten their own sentences, questionable "hair analysis" evidence or black defendants convicted by all-white juries. What's more, in the weeks after those stories appeared, two more men were freed from death row. That pushed the total to 13—one more than the number of inmates Illinois had executed since reinstating the death penalty in 1977.

The Porter case and the Tribune series were enough for Governor Ryan. On Jan. 31, he declared a moratorium on Illinois executions, and appointed a commission to see whether the legal process for handling capital cases in Illinois can be fixed. Unless he gets a guarantee that the system can be made perfect, Ryan told NEWSWEEK last week, "there probably won't be any more deaths," at least while he's governor. "I believe there are cases where the death penalty is appropriate," Ryan said. "But we've got to make sure we have the right person. Every governor who holds this power has the same fear I do."

But few are acting on it. In the wake of the Illinois decision, only Nebraska, Maryland, Oregon and New Hampshire are reviewing their systems. The governors of the other states that allow the death penalty apparently think it works adequately. If they want to revisit the issue, they might consider the following factors:

Race: The role of race and the death penalty is often misunderstood. On one level, there's the charge of institutional racism: 98 percent of prosecutors are white, and, according to the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, they are much more likely to ask for the death penalty for a black-on-white crime than when blacks are the victims. Blacks convicted of major violent offenses are more likely than white convicts to end up on death row. But once they get there, blacks are less likely than white death-row inmates to be executed because authorities are on the defensive about seeming to target African-Americans. The result is both discrimination and reverse discrimination—with deadly consequences.

The risk of errors: The more people on death row, the greater chance of mistakes. There are common elements to cases where terrible errors have been made: when police and prosecutors are pressured by the community to "solve" a notorious murder; when there's no DNA evidence or reliable eyewitnesses; when the crime is especially heinous and draws large amounts of pretrial publicity; when defense attorneys have limited resources. If authorities were particularly vigilant when these issues were at play, they might identify problematic cases earlier.

Deterrence: Often the first argument of death-penalty supporters. But studies of the subject are all over the lot, with no evidence ever established of a deterrent effect. When parole was more common, the argument carried more logic. But nowadays first-degree murderers can look forward to life without parole if caught, which should in theory deter them as much as the death penalty. It's hard to imagine a criminal's thinking: "Well, since I might get the death penalty for this crime, I won't do it. But if it was only life in prison, I'd go ahead."

Inadequate counsel: Beyond the incompetent lawyers who populate any court-appointed system, Congress and the Clinton administration have put the nation's 3,600 death-row inmates in an agonizing Catch-22. According to the American Bar Association Death Penalty Representation Project, in a state like California, about one third of death-row inmates must wait for years to be assigned lawyers to handle their state direct appeals. And at the postconviction level in some states, inmates don't have access to lawyers at all. The catch is that the 1996 Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act has a statute of limitations requiring that inmates file federal habeas corpus petitions (requests for federal court review) within one year after the end of their direct state appeal. In other words, because they have no lawyer after their direct appeals, inmates often helplessly watch the clock run out on their chance for federal review. This cuts down on frivolous appeals—but also on ones that could reveal gross injustice.

Fact-finding: Most states aren't as lucky as Illinois. They don't have reporters and investigators digging into the details of old cases. As the death penalty becomes routine and less newsworthy, the odds against real investigation grow even worse. And even when fresh evidence does surface, most states place high barriers against its use after a trial. This has been standard in the legal system for generations, but it makes little sense when an inmate's life is at stake.

Standards of guilt: In most jurisdictions, the judge instructs the jury to look for "guilt beyond a reasonable doubt." But is that the right standard for capital cases? Maybe a second standard like "residual doubt" would help, whereby if any juror harbors any doubt whatsoever, the conviction would stand but the death penalty would be ruled out. The same double threshold might apply to cases involving single eyewitnesses and key testimony by jailhouse snitches with incentives to lie.

Cost: Unless executions are dramatically speeded up (unlikely after so many mistakes), the death penalty will remain far more expensive than life without parole. The difference is in the up front prosecution costs, which are at least four times greater than in cases where death is not sought. California spends an extra $90 million on its capital cases beyond the normal costs of the system. Even subtracting pro bono defense, the system is no bargain for taxpayers.

Whether you're for or against the death penalty, it's hard to argue that it doesn't need a fresh look. From America's earliest days, when Benjamin Franklin helped develop the notion of degrees of culpability for murder, this country has been willing to reassess its assumptions about justice. If we're going to keep the death penalty, the public seems to be saying, let's be damn sure we're doing it right. DNA testing will help. So will other fixes. But if, over time, we can't do it right, then we must ask ourselves if it's worth doing at all.