|

| Reuters |

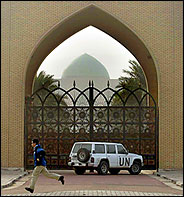

| A visit by U.N. inspectors to a presidential palace in Iraq tested their new mandate to search for weapons of mass destruction. |

BAGHDAD, Iraq, Dec. 3 — United Nations weapons inspectors took a close look around one of Saddam Hussein's many palaces today, in a further test of their powers to go anywhere of their choosing in the search for weapons of mass destruction.

Access to the palaces was a highly contentious issue in the 1990's, when the inspectors had to give advance notice of any such visit.

Today's visit, however, was unannounced, prompting Secretary General Kofi Annan of the United Nations to praise the inspectors for using their new authority and to assert that Iraq was cooperating with the weapons teams.

"There is a good indication that the Iraqis are cooperating, but this is only the beginning," Mr. Annan said. "They have to sustain the cooperation and effort and we will have to wait for the report of the inspectors."

Mr. Annan, speaking at the United Nations, would not comment on remarks by President Bush on Monday that his initial reading of Mr. Hussein's cooperation was "not encouraging."

At a political rally today in Shreveport, La., Mr. Bush repeated the kind of hard language he has used for weeks. "The issue is whether or not Mr. Saddam Hussein will disarm like he said he would," Mr. Bush said. "We're not interested in hide-and-seek inside Iraq. The choice is his. And if he does not disarm, the United States of America will lead a coalition and disarm him in the name of peace."

In the event of military operations, Turkey said today, it would open its air bases to United States warplanes. Asked if Turkish cooperation would extend to combat strikes, Foreign Minister Yasar Yakis said at a news conference in Ankara after meeting with Foreign Minister Jack Straw of Britain: "Yes . . . If you're talking about air bases, yes, those will be opened."

But he repeated Turkey's longstanding position that any military action must first be approved by a further Security Council resolution.

Turkey already allows American and British warplanes patrolling the no-flight zones in Iraq to use its air bases.

Mr. Annan's view on cooperation today seemed to be buttressed by the chief arms inspector, Hans Blix, who told The Associated Press that Iraq had not obstructed his teams in visiting any plants but that Baghdad must provide "good explanations" for having moved some equipment.

"Of course over a period of time, equipment can be moved but there must be some good explanations for it," he added, "and I'm sure that our people will inquire why was it moved and where was it moved."

Inspectors said on Monday that "a number of pieces of equipment" found at a top-secret missile development plant in 1998 had disappeared, despite a requirement under United Nations resolutions that they not be moved.

In today's visit, the inspectors were almost certainly struck by the opulence of the riverside Al Sajoud palace, but as usual they remained silent about whether or not they had found anything of concern.

They left without comment after about 90 minutes, but the Iraqis were eager to state their view of the visit.

"The Iraqi side was cooperative," Gen. Hossam Mohammed Amin, the chief Iraqi liaison officer, told reporters. "The inspectors were happy."

After the inspectors concluded their visit reporters were allowed inside the palace's spectacular entry hall, a three-story, eight-sided construction in carved white marble illuminated by an enormous gold-and-crystal chandelier.

Each wall was inscribed in huge gold letters with a poem praising Mr. Hussein.

"You are the glory," read one.

A terse United Nations statement issued on Monday did not specify the nature of the missing equipment referred to today by Mr. Blix. Inspectors made the discovery during a six-hour visit earlier in the day at a missile plant in the Waziriyah district of northern Baghdad.

Iraqi officials told reporters immediately after the inspection that the team had found nothing amiss.

But hours later, the inspectors' statement brought a sudden turn in what, until Monday, had been a series of tense but largely uneventful inspections.

The statement, brusquely worded, said the missing items had been placed under surveillance by monitoring cameras in 1998 and "tagged" with numbered labels signifying that they were not to be moved.

"In 1998, the site contained a number of pieces of equipment tagged by the United Nations Special Commission," the statement said, referring to the agency that was responsible for the inspections through most of the 1990's. The commission withdrew in the last days of 1998 before intensive American missile and bomb attacks. Now, the statement said, inspectors for the new United Nations monitoring agency found that none of the tagged items remained.

"It was claimed that some of these had been destroyed by the bombing of the site; some had been transferred to other sites," the statement said.

The Waziriyah plant, run by a state-owned company called Al Karama, was described in the statement as "one of Iraq's principal missile development sites."

Other missile experts have said that one of its main tasks has been perfecting electronic guidance systems for a short-range, liquid propellant ballistic missile known as the Samoud, one of several missiles thought to have been developed to carry biological, chemical or even nuclear warheads, as well as conventional explosives.

The compound of about a dozen hangarlike concrete buildings with 20-foot-high steel doors was rebuilt after it was largely destroyed in a United States cruise missile attack in December 1998. President Clinton ordered a four-day bombing assault, joined by British planes, after United Nations officials heading inspection teams that had endured years of harassment and intransigence by Iraqi officials ran out of patience with attempts to block their access to nuclear weapons sites and withdrew the inspectors. There were no further inspections until last week.

With Iraqi officials remaining silent on the issue on Monday night after the statement was issued, it was not clear whether the problem could be quickly resolved by the Iraqis' finding the missing equipment, or whether the day's events were the preliminary to a more threatening showdown.

Bush administration officials have said the United States might act on its warnings of military action against Iraq if it commits even a single serious breach of its obligations under the tough new weapons-inspection mandate passed by the Security Council last month.

Iraqi military officers who run the plant were in a feisty mood when reporters were admitted to the plant at midafternoon. They made a showpiece of a mound of tangled concrete and steel from the American missile attack, bulldozed into an area the size of two football fields.

"See that we have rebuilt everything that the evildoers destroyed," said Brig. Gen. Muhammad Saleh Muhammad, the plant's director.

But on the issue of the weapons inspections, the 40-year-old Iraqi officer was circumspect.

"It's not a normal thing, psychologically, to impose this indignity," he said. "But we will cooperate with the inspectors because they come here under a resolution of the United Nations. We want to prove to the world the falsehood of all the claims of Bush and Blair, that we have weapons of mass destruction." Of the day's inspection, he said, "They searched everything, our machinery, our computers, our documents, and they found nothing."

According to Central Intelligence Agency documents, the Samoud missile system that is the plant's main work — the Arabic term translates roughly as defiance — is not in itself a banned weapon under United Nations resolutions, since it has a declared range of less than 150 kilometers, or 94 miles. It is a scaled-down version of the Soviet-built Scud, which Iraq used extensively in its war with Iran. Some versions of the Samoud are said to have a range of as much as 590 miles.

But the main concern about the missile is its intensive development, including repeated flight tests since the Waziriyah plant was rebuilt in 1999. Experts see this development as aimed at technological improvements applicable to multistage missiles with a range of as much as 1,875 miles that Iraq is known to have at an early stage of design. C.I.A. experts have concluded that the Samoud still has major problems, including a shaky guidance system.