October 29, 2001

Once Again, Patriotic Themes Ring True as Art

By DEBORAH SOLOMON

|

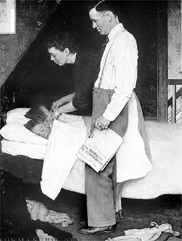

| (Curtis Publishing Co.) |

| Norman Rockwell's 1943 painting, "Freedom From Fear." |

|

| (AFP) |

| At a Yankee Stadium memorial, recalling a flag-raising at ground zero. |

PATRIOTIC art has never exactly ranked high on the list of aesthetic wonders, but who can doubt its appeal? It is hard to think of a painting in an American museum that can compete for visual immediacy with that famous image of Uncle Sam pointing his finger and sternly admonishing, "I Want You." The World War I recruiting poster is an inadvertent classic of American art, evoking the intense and tragic years when a generation of young men put on uniforms, boarded trains and promised their moms they'd be back soon while knowing they might never be back at all.

Not long after the twin towers fell and the tears started flowing, New York magazine ran a humorous cover illustration of Mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani decked out as Uncle Sam. You can glance nearly anywhere these days and see that patriotism has its own look, its own iconography, its own repertory of time- honored images. It is odd to think that my generation, the first for whom avant-garde art was not a moral offense but a subject to be diligently studied in college, now finds itself mesmerized by the landscape of patriotism. We who wrote term papers on Andy Warhol's soup cans and barely bothered to look at any flag that did not bear the signature of Jasper Johns are turning for solace to pictorial representations of honor, country and heroism that were born before we were.

For years, of course, such themes were disdained as artistically incorrect. The "American Century" whose advent was loudly proclaimed after 1945 took its cultural cue not from Peoria, but from Paris: It treated modernism as an assault on bourgeois values, and defined the archetypal American artist as a Jackson Pollock sort, a moody genius splashing out abstract pictures. Patriotic art, in the meantime, was presumed to refer to bronze statues of soldiers on horses, as stiff as mannequins and equally oblivious to the temper of the times. To proclaim an unironic interest in such art was to invite sneers from sophisticates, to be written off as a visual illiterate.

Yet the events of Sept. 11 and the weeks since have brought a sudden relevance and even respect to long- discredited images. The most striking example is the picture by Thomas E. Franklin, a 35-year-old staff photographer for The Bergen Record, that recently appeared on front pages around the world and made the cover of Newsweek. By now you have seen it: Three firefighters, their clothes and black helmets shiny with ash, gaze into a squinty-bright sky as they hoist a flag above the rubble of the World Trade Center.

The image became an overnight icon, and not only because it attests to the self-sacrificing courage of firemen. It also sends us back in time, evoking classic scenes of soldiers in battle. One thinks, in particular, of the photograph of Iwo Jima taken on Feb. 23, 1945, the four marines huddled together as they raise a flag above the island, their bodies and outstretched arms forming a pyramid that itself harks back to the balanced forms of Renaissance sculpture.

Not surprisingly, the photograph of Iwo Jima was later revealed to have been staged; it was taken a short time after the actual event occurred. Some people felt this made it fraudulent and also discredited the statue that was based on it, a mammoth bronze memorial that stands west of Arlington National Cemetery and remains the best- known monument of World War II. But such thinking is foolish. If art is a lie that tells the truth, as Picasso once said, the Iwo Jima Memorial certainly qualifies.

What, exactly, is patriotic art? In contrast to the School of Paris (think Picasso) or the School of New York (think Pollock), patriotic art might be regarded as the school of Washington, confining itself to eye-catching images that promote American institutions. It is commonly maligned as propaganda. It reached an apogee during World War I, when the federal government, seeking to mold opinion in a country where radio and television were not yet available, enlisted visual artists to advertise its cause. What they were selling was not soap or light bulbs, but the war effort and the government itself.

The Division of Pictorial Publicity, which was part of America's version of a propaganda ministry, wallpapered buildings and streets across the country with tens of thousands of posters, the most popular of which depicted Uncle Sam and his pointing finger.

That poster, by the way, was created in 1917 by James Montgomery Flagg, a prodigiously gifted illustrator who in some ways was an unlikely patriot. Flagg was a vivid character, a New York bohemian with striking features and a predilection for blond show girls. Unknown to the American public, he used himself as the model for his Uncle Sam. His recruiting poster takes an amorous come-on ("I want you") and turns it into a patriotic come-on.

HENRY JAMES once observed that Americans have "the reputation of always boasting and blowing and waving the American flag." Yet patriotic imagery need not be festooned with stars and stripes. Norman Rockwell, who did more to visualize the aspirations of Americans than any other artist of the 20th century, seldom painted the flag (as will be evident when a show of his work opens Saturday at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York). Instead he painted a country whose spirit remained abundantly intact despite two world wars and the Great Depression. In a time when anthrax attacks only intensify our yearning to return to normalcy, Rockwell's pictures of kids, dogs and uncranky grandmothers might be viewed as normalcy incarnate.

That's certainly the subject of his "Freedom From Fear" (1943), one in a quartet of wartime paintings based on President Roosevelt's rousing words. It shows two children snug in bed, their mother stooping to pull up their blanket, their father looking on, holding a newspaper whose partially visible headline announces news of "bombings" and "horror" abroad. To see the painting today is to see six decades slip away. We know now what it means to crave freedom from fear, the freedom to walk kids to school and toss a baseball in a park without feeling a shadow of trepidation darken the face of American democracy.

It would be absurd to pretend that patriotic art can give form to the full range and depth of human emotion. It cannot. It captures mainly one emotion: an appreciation for the values and rituals of American life. A few months ago that may have sounded corny, but it no longer does. As we continue to try to lend shape to feelings of national concern and affection, it would be a mistake to dismiss patriotic art as kitsch. It serves a purpose in the immediate present and — to judge from the example of Uncle Sam, Iwo Jima and two kids tucked into bed — at times can prove as enduring as any museum masterpiece.

Copyright 2001 The New York Times Company

![]()